In weather like this (namely, 90+ degrees, little-to-no wind, and me without air conditioning), beachy escapes are on everyone’s mind. Following is a rough timeline of how women have historically bared their flesh — or not — to enjoy the sand and sun.

Classical Times

In Classical antiquity swimming and bathing was most often done nude; only sometimes were there were coverings. Murals at Pompeii and ancient mosaics show women wearing two-piece wrap-around garments that resemble bikinis; these were worn for athletic pursuits as on the woman below, who wears the crown and cradles the frond of athletic victory.

19th century

But alas, western society did not long embrace the celebrated nude of the Greco-Roman era, and for many centuries afterwards, beachwear mimicked streetwear, and submerging oneself in water was generally limited to private experiences. It wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century when water sports, sun bathing, and swimming gained momentum again. Starting around 1830, a series of changes eventually led to the participation of women in sports and in specialized clothing being developed for those sports. The Industrial Revolution hearkened an age of train travel, the invention of the sewing machine and mass-produced fabrics enabled clothing in lower price ranges, and household machines and the development of labor unions gave the working classes more leisure time to indulge in travel, sports, and sun worship in exotic locales. The Dress Reform Movement (see my earlier post on Women, Pants, & Politics) advocated shorter dresses worn over loose harem trousers (the Bloomer Costume) that allowed women greater freedom of movement, as was needed for sports and swimwear. Exercise was increasingly prescribed by doctors and advocated by writers to maintain healthfulness; exercise programs even became an integral part of women’s college curriculums.

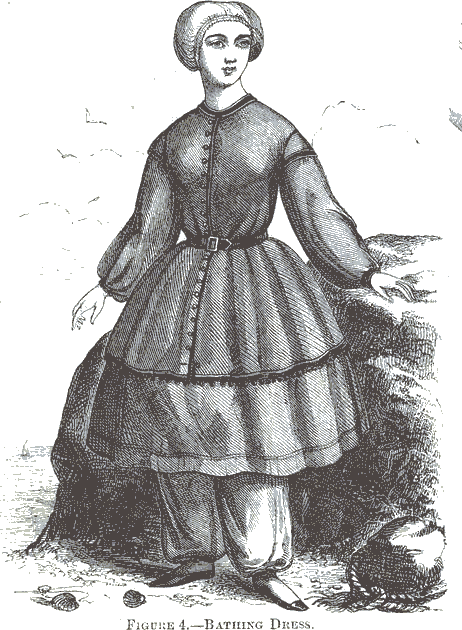

The typical 19th century “bather” wore black, knee-length, puffed-sleeve wool dresses, often featuring sailor collars for extra-special nautical costume effect (I say this somewhat facetiously, but it was probably used as a deliberate visual device to distinguish proper day wear from risqué sportswear), and worn over bloomers (derived from the Bloomer Costume) or drawers trimmed with ribbons and bows. Accouterments included long black stockings, lace-up bathing slippers that resembled ballerina slippers, and caps. As the 19th century progressed, bloomers and dress hemlines slowly but surely crept higher. Foundation garments being the basic (however questionable) mark of sartorial respectability, it wasn’t until the 20th century that women stopped wearing corsets underneath their bathing suits. Men had swim suits so closely resembling their undergarments that they made the distinction by wearing either black wool or black-with-stripes. You can see where how term bathing suit applied — the bathing costumes were made up of many layers that were worn as a cohesive ensemble.

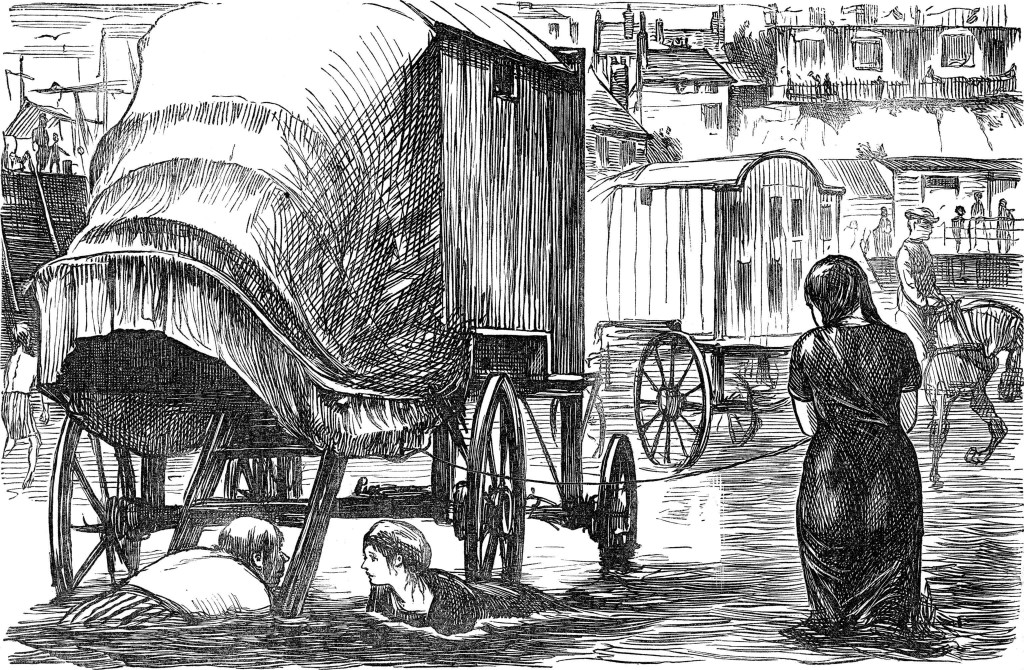

Beaches typically segregated the sexes, either with portions of the beach or different hours of operation. “Bathing machines” were used for additional modesty: they were dressing rooms on wheels in which women could change into their swimmies, were then wheeled out into the water by horses or people, and then were lifted out into the water to bathe. Below is an amusing cartoon from an 1870 edition of Punch:

Modest Old Gentleman (who has swum out to sea and whose bathing-machine has, in the meanwhile, been walked off by mistake). “Ahem! Pray Excuse me, Madam My Bathing-Machine I think.â€

And another cartoon from a postcard, closer to the end of the 19th century, showing the hilarious efforts men might exert to catch of glimpse of the women exiting the bathing machine:

1900s

By the turn of the century, bathing suits underwent a revolutionary change in styles as they ceased to be patterned after street wear and began to show a little more of the human form.

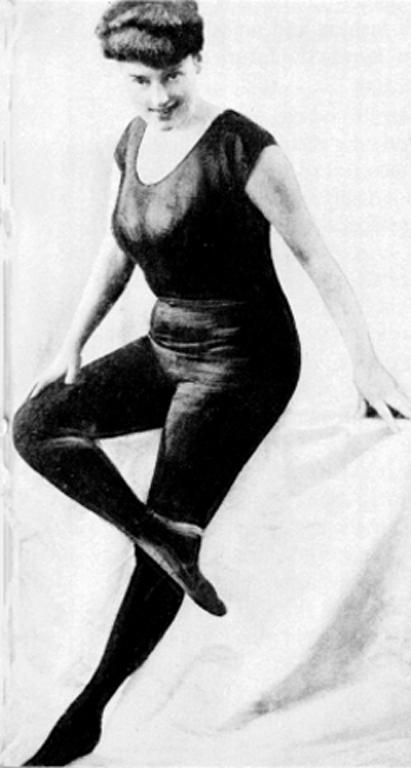

More athletic (and risqué) women pared down the bathing costume to be as form fitting as possible while still covering their bodies. In 1907 the Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman (1887-1975) visited the United States as an “underwater ballerina,” a version of synchronized swimming involving diving into glass tanks. She was arrested in Boston (my hometown is always Puritanical!) for indecent exposure because her swimsuit showed arms, legs and the neck. Kellerman changed the suit to have long arms and legs and a collar, still keeping the close fit that revealed the shapes underneath:

Laughable as this costume might be to our unshockable eyes, compare this to the body stockings worn by the prostitutes photographed by E.J. Bellocq (1873 – 1949) in Storyville, New Orleans’ Red Light district circa 1912. It’s hard to see, but this woman is wearing a full white unitard of the variety worn by burlesque performers (it’s important to note that only dark colors were used in early bathing costumes exactly because they were to be visible, and not to even give the illusion of nudity as this one does):

1920s

The swimwear industry took off in the ’20s. As athleticism and slimmer figures gained increasing fashionableness (see my post on Bicycle Chic and Athletic Aesthetic), knitwear companies expanded their market from sweaters and underwear to include swimwear. With its beautiful beaches and warm waters, it’s unsurprising that the West Coast emerged at this time as a hotbed of swimsuit manufacturers with Catlina, Cole of California, and Jantzen all setting up shop there. The West Coast was not coincidentally the home of burgeoning Hollywood, and this proximity led to the early adoption and wide dissemination of new bathing suit styles in popular films and publicity photographs. Mack Sennett (1880-1960) was a slapstick comedy director whose films frequently featured his titillating “Bathing Beauties,” pictured below:

The boyish figure favored in the 1920s affected the style of the bathings suits, which were shorter and very much mimicked men’s bathing trunks. (Note also how these bathing suits resembled the mod miniskirts of the ’60s, yet to come.) As ever, when hemlines are raised and garments tightened, modesty becomes a priority for moralists. Below is a 1922 photo of Washington policeman Bill Norton measuring the distance between knee and suit at the Tidal Basin bathing beach after Col. Sherrell, Superintendent of Public Buildings and Grounds, issued an order that suits not be over six inches above the knee (it looks like someone might be in trouble!):

1930s

Knit wool swimsuits, though infinitely more practical than the bathing costume of the 19th century, were still imperfect. They became waterlogged, droopy, and heavy when wet, weighing an average of 20 pounds (owning a vintage wool bathing suit, I can attest that the sagginess is both uncomely and uncomfortable).Technology development stepped in, and the elastic rubber fiber Lastex was invented in 1934. This new material, with natural fibers surrounding a rubber core thread, was used in undergarment corsetry and swimsuits.

The close proximity between the swimsuit manufacturers and Hollywood continued to influence each other. As Lizzie writes in her excellent piece on swimsuits, “Stars and Hollywood designers were used to advertise and promote the latest in swimwear.” Below is Carole Lombard, brash comedienne and lucky wife of Clark Gable. You can see the swimsuits are tighter, shorter, and introduce glamor to what had been previously been somewhat clunky sportswear:

Though Jean Harlowe’s white number is even skimpier (and plays with the suggestion of nudity with its white fabric on white skin), note that it is only the necklines and silhouettes that are played with — the leg hemlines remain solidly and straightly at crotch level, no higher.

1940s:

Esther Williams (1921-), who had made a somewhat oxy-moronic career for herself as a soloist synchronized swimmer in film musicals, signed a modeling contract with Cole of California in 1947 which also included an annual swimsuit design named for her. Here is a nice montage (feel free to turn the sound off) where she actually pretends to be the aforementioned Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman, among others, in The Million Dollar Mermaid (1952).

If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times: war affects fashion. U.S. factories are often commandeered by the military during wars, using their existing facilities to produce supplies for the war effort; this was true of the swimwear industry during World War II, as well. Fabric rationing led to sleeker, more closely tailored silhouettes in day wear, and sanctioned increasingly skimpy swimwear: as Lizzie points out, “The US government actually mandated that bathing suits were to be made with at least 10% less fabric, and so the midsection was eliminated” (keeping that scandalous orifice, the navel covered!). French engineer-turned-swimsuit-designer Louis Reard created the “bikini” in 1946, macabrely named after the concurrent nuclear bomb test site on the Bikini Atoll, though some say it was an allusion to the explosive effect the midriff-baring bikini would have on viewers. A year after it was released in France, Reard’s bikini was released in America, though its sales were not so great, and was even outlawed in some states as a result of its scantiness.

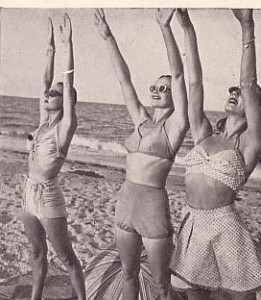

More popular in the colonies were slightly more modest bikini tops with shorts, which actually crossed the line into non-swimming casual wear.

1950s

Post WWII, there was a so-called return to femininity with Dior’s “New Look,” emphasizing curves with yards of skirt fabric, torpedo bras and stiff bodice corsetry. Swimsuits conformed to this ideal too, often with stiff strapless bodices, cinched waists, and apron-like skirts that fell over an invisible skimpier under-layer. More colors than ever were incorporated into swimwear, too, with the return of all America’s factory and supply resources.

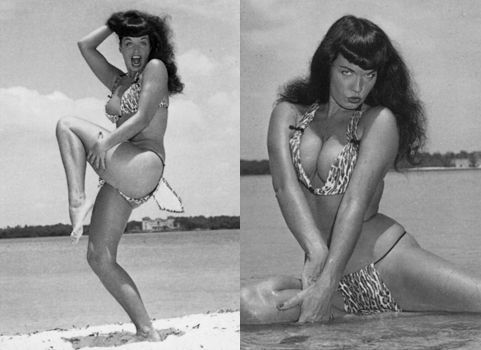

On the flip side, pin up girls were regularly drawn and photographed in swimsuits, as cousin of the negligee. Below, Bettie Page models some racier swimwear, always designed by herself:

1960s

The 1960s heralded the dawn of the Sexual Revolution, the generation that rejected their parents’ prudish impact in the ’50s (Bettie Page very much excepted). This was the first time the female bathing suit moved its hemline above the crotch to encircle the legs rather than square them off. Bond Girl Ursula Andress became an iconic figure (literally and figuratively) in this bikini from Dr. No (1962):

Below is the publicity shot for Rudy Gernreich’s infamous topless “monokini:”

Even as it created a fashion sensation, it’s unclear how many women actually bought and wore this number, scandalous even today. Compare the artsy studio photo above to a photo of a model in public (with a billboard man leering at her no less!):

1970s, ’80s, & ’90s

The 1970sembraced less structured clothes and swimsuits, exchanging the stiff elastic ruching and bullet-bra cones for simpler, softer patterns that conformed to the wearer’s body rather than the other way around. The waistline was lowered to hover at the widest point of the hips, rather than at the thinnest point of the waist. The fabric was often unlined, exposing the outlines of nipples (see this hilarious ad for nipple enhancing bras from that period!), as can be seen in the iconic poster of Farrah Fawcett:

The ’80s embraced exaggeration in all fashion: huge shoulders, tiny waists, big hair, polychromatic, etc. Bathing suits took on a distinctly geometric feel, often with strategic cutouts for some interesting looks that must’ve created creative tan lines.

Baywatch reigned the small screen in the 1990s. Everyone remembers the Baywatch babes running in slow motion in their bright red, high-cut, low-cut lifeguard swimsuits:

1990s to now

Since the 1990s, bathing suits have more or less leveled out. Leg holes have generally lowered to a less crotch-pulling height, but we’re in the throws of a nouveau ’80s, so I’ve seen a resurgence of those cutout bathers.

Bathing suit technology has been in the headlines in the past decade due in great part to the press everything Olympics-related generates. Though it’s too expensive to be used for leisure beach activity, Speedo’s LZR swimsuit, invented in 2008, has caused much ruckus among competitive swimmers in recent years. Its corset-like sleek design (it’s said to necessitate 3 people to help a swimmer get into it!) and lasered seams eliminated so much water drag and shaved precious milliseconds off speeders’ times that it was ultimately banned as a kind of performance enhancer that competitors who had non-Speedo sponsors could not wear.

And on that note, I’m off to my local pool to escape this cursed heat, in my Esther Williams vintage-style swimsuit.

Further Reading:

- The Shifting Tides of Seaside Postcards – bathing suits as seen in vintage postcards (you need to scroll halfway down the long page to find the right post)

- The California Swimsuit

1 comment

Lynne Reiss says:

Jul 22, 2010

I am always impressed by what you know and how amusingly you convey it to the rest of us.

P.S. I remember those heavy wool bathingsuits. (Maybe I can use that as an excuse for my lack of swimming abilities…