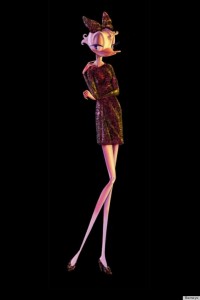

I recently came upon a light news item that caught my eye: following a partnership between Disney and Barneys department store, beloved Disney cartoon characters have been augmented to resemble fashion sketches:

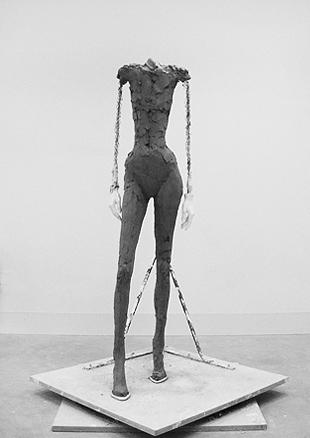

Though many of us in the fashion world are used to seeing these hyper-elongated bodies, impossibly willowy limbs, bodies whose legs consume 3/4 of the entire body, in various stances of elegant / coy / alluring indifference, there’s nothing like seeing a familiar non-model — or family cartoon — rendered as a fashion plate to jolt you out of your complacency of acceptance of these beauty standards. Warping cartoons into conforming to of-the-moment beauty standards is especially pernicious since many cartoon characters are specifically bred for consumption by children, whose beauty concepts, self-esteem, and bodies are still very much in formation.

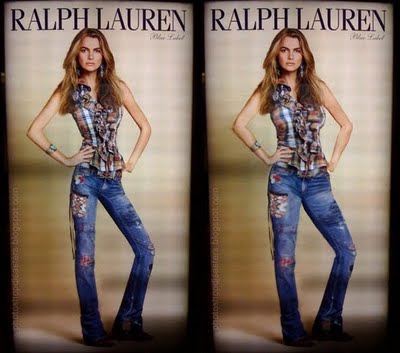

Photoshop, that ubiquitous digital editing software, has facilitated image alteration, and in our quest for perfection in body and art, we feel free to change colors, brush out shadows and unsightly bulges, smooth skin tone, plump up eyelashes, etc. Celebrities want to look the best they can, and fashion and cosmetic companies want their models to represent their brands in the most attractive light to elicit envy and admiration (ideally culminating in product sales). But airburshing gets sticky when you start shaving entire pounds off people, lightening skin tone, and eliminating all signs of natural aging. Because women are used in advertising far more than men, this perpetuates, if not galvanizes an arms race of sorts to valorize unusually thin, atypically busty, wrinkle-and-grey-hair-free Caucasian “women” who are often under the age of 20, or meant to look like they haven’t aged since then. Britain’s Advertising Standards Authority has, in recent years, banned several airbrushed ads that seemed especially egregious in their unrealistic depictions of women, though thousands of other questionable ads did pass ASA’s standards — and that’s only Britain. America has no such watchdog organization, though the American Medical Association is trying to “take a stand against rampant photo retouching, declaring the practice detrimental to your health….”

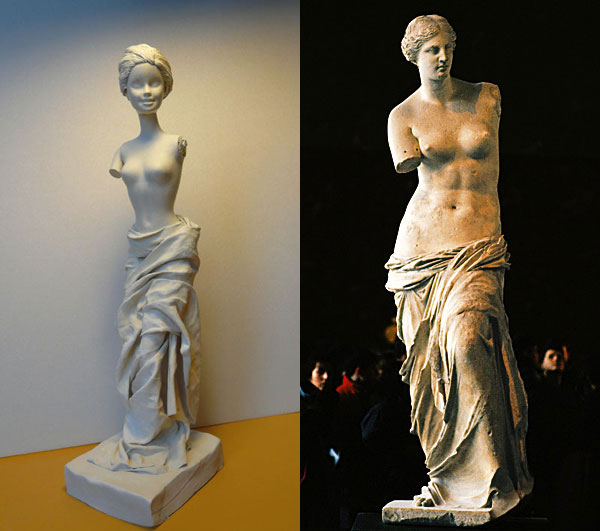

Filippa Hamilton’s controversial Ralph Lauren ad reminds me of Jocelyne Grivaud’s humorous depiction of Venus de Milo as Barbie (I should note that this was intended as an homage to Barbie, rather than commentary on unattainable beauty standards literally handed to little girls; but even this disparity demonstrates the hyper-subjectivity of images, does it not?).

So ok, depictions of grossly distorted people — generally women — in fashion illustrations and magazines can be disturbing, certainty contributing to a culture in which Thinspo (or “thinsporation”) is a viable meme of unhealthy, unattainable aspirations. In her awesome article “Mainstream Feminism’s Demand for Realism: On “Fotoshop by Adobé,†aesthetics, and posthuman feminism,” blogger Robin refutes the feminist impulse to condemn post-production editing, as no image is unbiased:

“Image alteration is itself neither good nor bad, neither feminist nor anti-feminist. I think instead we need to make people even more familiar with image alteration, so they can spot it when they see it…. We shouldn’t get rid of art, or demand that images not be, uh, images. We just need to better image literacy.”

Furthermore, the manipulation of physical appearances in imagery is hardly a new phenomenon. The ancient history of portraiture has verily depended upon tweaks and conformity to contemporary beauty standards: the livelihood of the portrait artist has depended upon walking the precarious line between creating a recognizable likeness of a person, while smoothing out her less desirable physical attributes, so the sitter wants to pay and recommend the artist to their wealthy friends. By many accounts, Queen Elizabeth I had thinning hair, smallpox scars, and bad teeth. More than simple vanity (which was certainly at work too), a Wikipedia author posits that “From the 1570s, the government sought to manipulate the image of the queen as an object of devotion and veneration…. The management of the queen’s image reached its heights in the last decade of the reign, when realistic images of the aging queen were replaced with an eternally youthful vision defying the reality of the passage of time.”

Around 1592, Isaac Oliver began a portrait miniature of the queen, that was to be a template for currency. It’s hard to see in reproductions, but historian Roy Strong hypothesized that this image of 59-year-old Elizabeth was a little too close to flawed reality with her sunken eyes, wrinkles, and thin lips, and was abandoned before completion. In contrast, the “Rainbow Portrait” of QEI a decade later was apparently a success: but does that woman look like a 67-year-old who lived in a time of <ahem> questionable hygiene? Was this artistic license or extreme image manipulation? If the sitter encourages the artistic liberties, is that more acceptable, somehow? How does Queen Elizabeth’s propaganda of herself as ageless Monarch Supreme differ from ads selling a physical product or lifestyle?

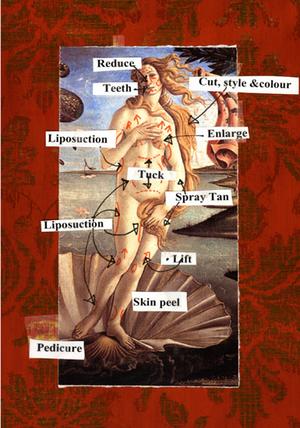

The — dare I say — beauty of cartoons, photos and paintings is that they need not be limited by pesky details like real-time aging or real-world anatomy. One might argue that paintings of Lizzy here didn’t give false hope to all Western European women that they could look as weirdly dramatic, with high foreheads (considered beautiful at the time), rigidly triangular torsos, and sculptural red curls…. But those were all physical constructs too, which women who could afford them indulged in as well (and were certainly influenced by the Queen’s style precedent). Manipulations of the body and face are as ancient as human civilization, including hair plucking / shaving / waxing, wigs, makeup (much of which has been and still is made of ingredients later discovered to be toxic), corsets, heeled shoes, padding, etc. (all of which have been used by men too). Technology and surgical advancements have opened new worlds of body manipulation, though these desires certainly existed before.

.

Phillip Toledano‘s book A New Kind of Beauty is a collection of classically stylized photographs of cosmetic surgery subjects. Disparagingly dubbed “Botox Botticellis” by the press, on his website Toledano challenges, “Is beauty informed by contemporary culture? By history? Or is it defined by the surgeon’s hand? Can we identify physical trends that vary from decade to decade, or is beauty timeless?” Why are so many people quick to critique Toledano’s art, and to condemn his subjects as victims of our supposedly superficial culture? Did all women of the Renaissance have tiny, shelf-life breasts and high bellies? No, this was a deliberate manipulated filter of painters to portray or capture the beauty standard of the day. It has been pointed out (perhaps in a couched critique of the subjects themselves) that the “Botox Botticellis” begin to resemble one another– but is this so different from the paintings and sculptures of Medieval women that end up resembling one another (the sharp Anne Hollander addresses this in several excellent books on art and fashion)?

What makes Cindy Sherman portraits — highly stylized, highly manipulated with makeup, wigs, padding, image editing software, you name it — palatable to general audiences, versus Phillip Toledano’s? Is it because Sherman’s crude makeup techniques and prosthetics are so obvious we don’t feel tricked? We understand it is “art” and not meant to adhere strictly to reality, or manipulate us? Except successful art, I would argue, should elicit a strong response, pleasant or unpleasant. Why do expectations differ based on whether we see images on a museum wall or in a magazine? Robin stresses that all images, including advertisements and not simply fine arts — have no moral obligation to the public to be “accurate,” and in fact they almost always depict a fantasy. Furthermore, attributing grandiose, wildly biased words like “good” and “bad” to things like “natural” or “fake” is an unhelpful fallacy. Plagues are “natural;” heart transplants are “artificial;” are they “good” and “bad,” respectively?

In his Spring/Summer 1999 collection, Alexander McQueen used double-amputee athlete Aimee Mullins to model a pair of ornate hand-carved legs that merged shins into high heeled shoes, obliterating distinction between the body part and the fashion accessory. Far from being disabled, there has been controversy surrounding the advantage that Aimee Mullins’ prosthetic legs may give her over mere human bone and muscle, and yet according to the assumption that natural = beauty = good, she does not qualify, nor do the McQueen leg-boots (does it count that the legs are “natural” wood?). Though the prosthetic leg exhibits extraordinary craftsmanship, I kinda wish McQueen had abandoned the shape of an ordinary leg altogether — made them lumpy, or wildly asymmetrical, or the legs of an animal that would make it impossible not to notice the fake-ness, and to celebrate that deviation.

You might have heard of the bizarre recent fad of young girls actually trying to attain the (previously) unattainable figures, glassy eyes, enormous perky breasts atop the waif-thin figure modeled after anime characters or Barbie. Meet 19 year-old Anastasiya Shpagina, a.k.a. “Anime Girl,” who whittled her 5’2†frame down to around 90 lbs; plumped up her breasts with a boob job, and spends an hour on her makeup daily. She currently uses contacts and makeup to achieve the glassy stare, but Daily Mail reports she plans to undergo some sort of procedure to permanently make her eyes appear more like an anime character’s. Her friend Valeria Lukyanova, a.k.a. “Barbie Girl,” has undergone similar efforts to achieve a realistic likeness to that plastic doll of unrealistic proportions. These girls are clearly not trying to look “natural.” Robin writes that many so-called feminists have

“a rigid conception of what counts as ‘real’ human female embodiment, and marginalizes women (and men, and trans/genderqueer people) who practice alternative forms of embodiment, and who often rely on artifice to maintain their bodies. What’s so bad about plastic skin? Prosthetic limbs have plastic ‘skin’. What’s so bad about artificially crafting your ideal face with makeup, or even surgery? Transwomen and transmen do this.”

.

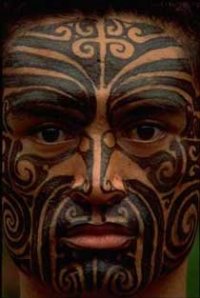

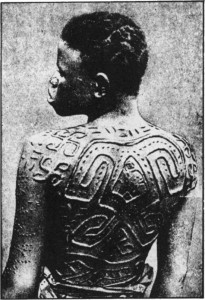

“Extreme” cosmetic surgery is where a lot of people start to feel icky. But body modification, too, is an ancient art — tattoos and scarring have been executed by the New Zealand Maori, Australian Aborigines, Japanese, and African tribes as literal marks of power, status, and beauty.

So where do we draw the line in body alteration? Permanence? (Tattoos can be removed now, and image editing leaves the original body untouched.) Age minimums? (Maoris and African scarring rituals begin at a young age.) Necessity? (Slippery slope, this one.) You can choose for yourself, ideally without getting on a moralistic high horse, indulging in so-called “feminist” hyperbole, or blaming contemporary technology or image makers. Humans have always sought to alter our bodies, we’re merely continuing that exploration with 21st century ideals and methods.

.

Further Reading:

1 comment

BarbaraK says:

Aug 21, 2013

Provocative and an all-around good read. Thank you, Tove.