Last week I watched the movie Coraline (2009), directed by the stop-motion animator master Henry Selick who achieved recognition for his collaboration with Tim Burton in The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993). I was kind of blown away by his latest effort; it succeeded on many levels, but for the sake of this blog I’ll limit my enthusiasm to the crafty parts.

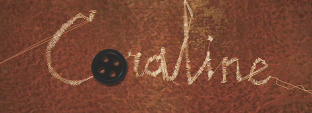

The loving attention to hand crafts — and needlework in particular — starts immediately with the opening credits which are done in a font that mimics embroidery, complete with visible stitches and deliberate loose threads dangling off the names:

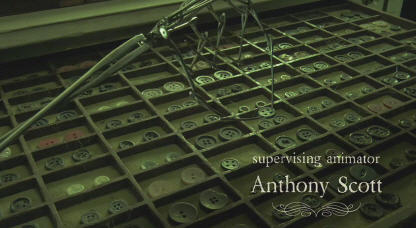

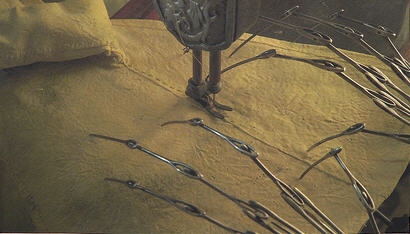

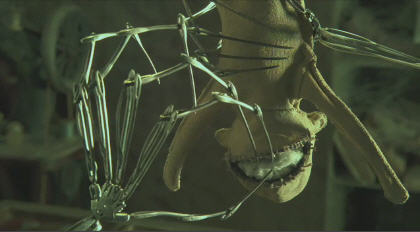

The next 1 ½ minutes of credits include careful closeups of a doll being undone, unraveled, un-stuffed, taken apart stitch by stitch, and then reassembled (note the creator’s hands are composed of needles themselves):

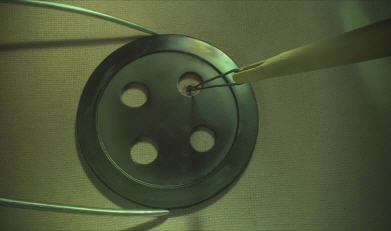

There’s a lovely shot of a button drawer being pulled out and poured over,

a needle poking through rough cloth (you can see every fibre in 3-D!) and sewing the selected button on,

a needle poking through rough cloth (you can see every fibre in 3-D!) and sewing the selected button on,

reusing the limp burlap chassis to meticulously create another doll with variations that make it resemble Coraline, down to her raincoat:

REPETITION. REPETITION.

Just as puppet masters created Coraline puppets in multiples with slight clothing, expression, hair and rumpled variations to make the movie, duplication and cloning are visual motifs within the movie. Coraline’s mother picks out a mass-produced gray school uniform among a rack of identical uniforms,

all the neighbors have collections of identical animals: the burlesque sisters with their Scottie dogs (3 living, many more stuffed on shelves),

and the Amazing Bobinski with his circus mice:

And when Coraline’s parents go missing, she touchingly tucks herself into bed with crudely handmade dolls of them, formed out of pillows with dad’s glasses and mom’s neck brace (a doll making dolls of other dolls):

Looking at the plot, we see this theme of multiplicity is a satisfyingly consistent one: the neighbor kid Wybee’s grandma has a(n evil) twin sister; the entire concept of the Other Mother and Other World with nearly identical houses, and gardens and neighbors echo and compliment each other within the framework of the story. These devices create an eerie mirrored alternate world like those in a Borges story, but also relate to the duplicate film sets (which were actually constructed by set builders, not created digitally), dolls, clothes, etc., behind-the-scenes. The evil twin / menacing other world is not exactly original subject matter for suspense-horror films which often tap into fears of duplicitousness and two-facedness, but I particularly love how the duplication appears in front of the camera and behind it in Coraline.

CRAFTINESS

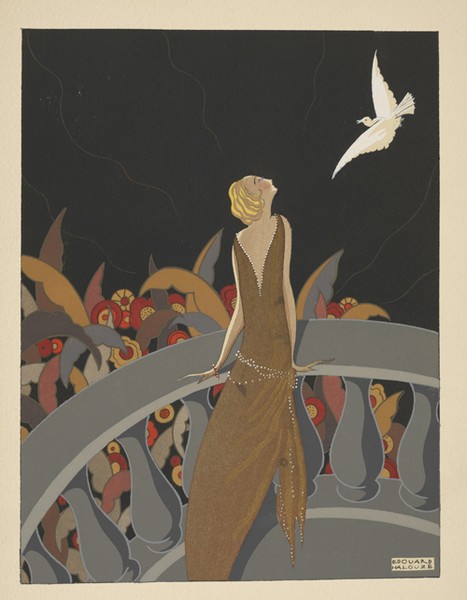

Crafty, homemade objects are featured prominently. Coraline’s Other Mother cooks homemade meals, creates hand-sewn outfits for her, etc. Coraline (and the viewer, by extension) recognizes these as signs of affection. Interpreted as labors of feminine love at first, they are revealed to be sinister, employed as a trap. When the Other Mother reveals her true physical form as a terrifying spider with needle hands (the same needle hands that seemed to lovingly craft the doll in the film’s opening sequence), it calls to mind the sculptures of Louise Bourgeois. In her “Cell†series, Bourgeois created mini houses out of found objects like discarded doors and grating and filled them with objects related to feminine domestic stereotypes like sewing supplies, clothes, etc.:

Louise Bourgeois, interior of “Cell VII” (1998). Note the eerie hanging undergarments and miniature house.

Another Bourgeois recurring visual motif is spiders, representing her own mother and universal stereotypes of mothers (one is actually entitle “Maman“) and exploring their creepiness and yet comfortable familiarity and harmlessness:

Louise Bourseois, “Spider” (1997). Note the cage / house enveloped by the enormous arachnid, and scraps of fabric clinging to the sides contribute to the mother / domicile theme.

Compare Bourgeois’ large but protective Spider to Coraline’s Other Mother as a distinctly evil spider who deploys a web not to catch pesky insects but to entrap Coraline herself:

In the final scene of Coraline, domestic bliss is achieved by unifying her family and the previously indifferent neighbors in the act of planting tulips, a pared-down version of domesticity, handiness, and community. They’re not perfect — Coraline’s mother complains about the dirt, Bobinski pulls out tulips bulbs to replace them with beets, and the end result is not the stunning spectacle of the Other World’s garden — but it is a more realistic picture of imperfect homeyness.

Now allow me to lay some incredible fun facts on you about the meticulous crafty creation of this film:

- To construct 1 puppet, 10 individuals had to work 3-4 months.

- About 45 of Coraline’s pajamas were screen painted with printed patterns where every dot had to line up along the seams of every frock in precisely the same place for consistency.

- For the character of Coraline, there were 28 different puppets of varying sizes; the main Coraline puppet stands 9.5 inches high.

- All fabric was hand woven or hand knit to achieve the correct scale.

- The only leather the production could find that was thin enough to make the doll shoes and Mr. Bobinsky’s boots came from antique Victorian gloves.

- Buttons and zippers were also handmade for the film to suit the scale.

- Costumers used pins, surgical tools and tweezers to construct the garments.

- Each of Coraline’s star sweaters took 6 weeks to 6 months to design and knit on knitting needles like toothpicks. (On the website in Coraline’s room there is a film short on miniature knits. It will blow your mind a little.)

HISTORY OF SEWING IN THE HOME

Coraline tapped into the familiarity we have with women performing acts like cooking, cleaning, and sewing: the audience presumably watches the film with knowing amusement as Coraline’s father makes a dinner which resembles the gelatinous, sludgy meals from Better Off Dead (1985). We learn that Coraline’s mother is a good cook but has prioritized professional work and has relegated the dinner chore to the inept (though good-intentioned) father. The Other Mother then lures Coraline with elaborate, beautifully presented meals and a homemade sweater ensemble.

There is a rich history binding women to sewing. “A woman who does not know how to sew is as deficient in her education as a man who cannot write,” Eliza Farrar wrote in The Young Lady’s Friend (1838). Creating, altering and mending the family’s clothing and household textiles were domestic duties that kept most 18th and 19th-century women tethered to their sewing baskets; until the late 19th century nearly all clothing was made in the home. According to Godey’s Lady’s Book, it took about 14 hours to make a man’s dress shirt and at least 10 for a simple dress. A middle-class housewife spent several days a month making and mending her family’s clothes even with the help of a hired seamstress.

Sewing wasn’t all drudgery, though. Needlework served utilitarian purposes in the home, but also allowed women to communicate and assert their individual identities, beliefs, and aspirations with creativity and skill. The anticipation of weddings and births fueled creative energy and inspired impressive handiwork which was often functional — but not always — as in samplers which showcased a woman’s cross-stitching dexterity by forming alphabets in varying typefaces, geometric borders, and picture scenes. Linens, blankets and other handmade textiles made up the bulk of a girl’s hope chest (a.k.a. “marriage chest”), preparing her for her household duties as a wife and serving as advance proof of her sewing skill and worth as a woman and future matriarch.

Early 19th century sewing sampler stitched by Elizabeth Lyle when a young girl. The text in the center reads,”Elizabeth Lyle worked this in the eleventh year of my age. In the morning think what you have to do. And at night ask yourself what you have done.”

Sewing circles were commonly formed by women, comprised of neighbors and relatives who would gather at a house and work on their sewing chores together. Women would sometimes swap portions of their own work with their friends who were particularly adept at a specific tasks. This happily merged what could be lonely drudgery with pleasurable socializing and political discussion (though the latter is rarely acknowledged).

Sadly, sewing was often taken for granted as a skill — seamstresses were perceived as unimaginative lackeys who just followed instructions that any person might perform, and not as visionaries who could conceptualize how to take two-dimensional materials and connect them to form three-dimensional structures that envelope a body and yet can be gotten into easily, who possessed the skill to adapt techniques to various textures and weights, to say nothing of the artistic choices of color, style, and fit. Appreciation aside, there was a drastic interruption of this centuries-old tradition in the mid 19th century.

It wasn’t until the House of Worth (founded in 1858) when a man took the reigns of dressmaking, removed it from the home and created a pampered, decadent purchasing experience, that sewing took on any cachet or respect as a profession (see my earlier post on The Tea Gown in Fashion and Art for more on the House of Worth). The Industrial Revolution heralded the invention of the sewing machine (patented by Elias Howe in 1845), cheap labor and the growing factory system, standardization of sizes, and outcropping of distribution methods like apparel and department stores, all of which contributed to an increase in demand of ready-to-wear garments. This was the beginning of consumers’ expectations for hyper-accelerated turnaround of new styles, necessitating ever-briefer time between designers’ visions, prototype creations, and mass market availability. It could be argued that the sewing machine eased women of much of the time consuming burden of clothing their families, but a contrary view is that the sewing machine snatched a labor of love, pride, and skill from women, not to mention the social community bonding. And though it’s distasteful to many modern women to think of being trapped in their houses all day, it was a small leap from the workrooms of House of Worth to the factories and notoriously dangerous conditions of garment factories (like the infamous Triangle Factory), exploiting the poor. Though sweatshops certainly exist in America today, many more are in developing countries with desperate-and-therefore-cheap labor forces, doubly exploited by consumer-hungry countries abroad and their own government systems which do not protect them with worker’s rights addressing age minimums, hour maximums, safety standards, etc.

In terms of household implications, the sewing machine was only the first of many labor-saving devices for the home (partially by altering sewing from a home activity to a factory one); washing machines, dryers, dishwashers and vacuum cleaners all made housekeeping easier and cut down the work time required. An important consequence of all this labor saving has been the diminished woman’s role as household manager. This gradual loss of status helped undermine the satisfaction many women formerly found in the homemaking role and encouraged them to seek more demanding employment in other places, as we see Coraline’s mother has chosen her profession over domestic work. In most industrialized countries these days, sewing, needlework, knitting, crocheting, quilting, etc. have been relegated to niche markets (still mostly women) who have self-consciously resurrected the skills for hobby, not generally necessity. This is why we all understand how Coraline is taken in by her Other Mother’s handmade overtures.

I loved Coraline not only because it was a good, creepy story, but because its meticulous production methods showcased the hand-made theme present in the narrative, a far cry from the digitally created worlds of almost all current animation (which can absolutely be well done too). I like, too, how the simple black button icon of Coraline is a symbol of sewing and domestic familiarity twisted beautifully into a tool of sinister manipulation.

Further Reading:

- “The Culture of Sewing: Gender, Consumption and Home Dressmaking†by Barbara Burman

- “History of Sewing†online study guide

- “Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times†by Elizabeth Wayland Barber

- “The Making of Coraline” in Extra Features on Coraline DVD

- “How the Other Half Lives” Jacob Riis photographs of exploited poor Lower East Siders, NY

1 comment

Diane Bell says:

Jul 3, 2010

Please note, Wybee’s grandmother’s twin sister was not evil, but an early victim of the other mother, which is why Wybee was forbidden to visit the house Coraline lived in. In the opening credits, the doll the other mother transforms into Coraline is the likeness of the Grandmother’s twin as a child — the doll that the grandmother kept in a trunk after her sister disappeared. Wybee found it and showed the doll to Coraline because it looked so much like her. Cool, right?