My Godmother sent me this brief article on David Hockney‘s withering opinion on artists such as Damien Hirst who rely upon assistants to “do the work” — Hirst has only painted five of the 1,300+ “spot paintings” in existence, and he was quoted as saying that many of his spot paintings are produced by others “because he finds it boring to do the detailed work.” I think it’s easy to cluck and tsk and agree with Sir Hockney — how could an artist relinquish responsibility for creation and/or execution to others? My stars, I bristle at the very suggestion!

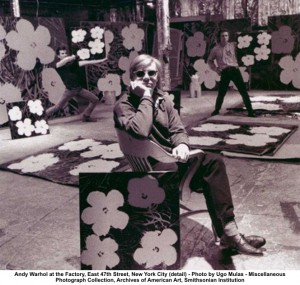

But let’s step back for a moment and entertain the idea that this may actually be a matter of context and expectations. Some arts — painting in particular — have a history of being conceived and executed by one person. However, even that is not a hard and fast rule. Andy Warhol famously oversaw assistant-produced art at The Factory, and in fact the decentralization and democratization of the creation process was essential to the concept, which often involved the repetitious and machine-like branding of store items. His art could be made and reproduced by practically anyone. Warhol hired Gerard Malanga as his assistant in 1963, among others, and together they made some of “Warhol’s” best known silk screened works of art. Below you see Malanga working with Warhol on the left, and two unidentified assistants literally blend into the background while playing with the collaborative Flowers while Warhol commands center stage:

There are plenty of artistic professions where it is actually expected that a work is produced with the help of — or even in its entirety by — workers other than the name attributed to the final design. Architects work with teams whose members specialize in interior stairwells and elevators, energy efficiency, etc.; not every architect involved in the highly complex work of designing, say, the Whitney Museum’s expansion, will be known by the public: Renzo Piano‘s will be, though. And if we’re talking about the physical production of art (or pawning it off, as the case may be), architects do not physically build “their” buildings at all; they simply provide the plans.

This is similar to the work of Sol LeWit who has made his name as an artist by redefining the role of the artist as more of a designing architect, providing plans that disseminate the art-making to anyone who cares to follow his instructions. In the late ’60s, LeWit began a series of now-famous wall drawings, providing clients and galleries with plans for murals they could make for themselves at any scale, with any colors, on any surface, displayed anywhere — but still attributed to Sol LeWitt. Some more exacting LeWitt instructions are miniature versions on paper; other, more conceptual works are described with words, as with Wall Drawing #65. Here are the instructions:

“Lines not short, not straight, crossing and touching, drawn at random using four colors, uniformly dispersed with maximum density, covering the entire surface of the wall.“

…and the product, seen in progress at the National Gallery of Art:

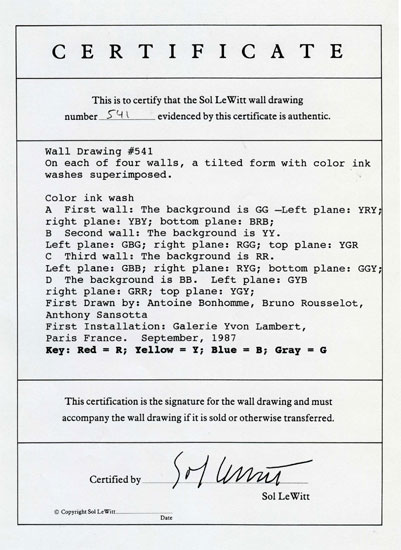

Though a central point of this art is that anyone may create or finish “Sol LeWitts,” the instructions, minimal as they are, are proved authentic by being presented on numbered certificates which interestingly include previous installations of that work, as seen below:

Street artist JR deliberately includes local residents of the often violent and/or impoverished areas he targets for his building-sized photo installations, acting more like a project coordinator than a street / graffiti artist. Like LeWitt, JR encourages people to take his ideas and make them their own — in fact, this is essential to his work. He gained recognition with his posters of eyes and close-up portraits of residents pasted along war-torn borders or poverty-stricken neighborhoods and countries. JR’s latest efforts take this a step further by executing even less of the actual art production himself. In the economically depressed (and notoriously rough) Hunts Point neighborhood in the South Bronx, he collaborated with the Hunts Point Alliance with Children to engage the community by making residents responsible for beautifying and “taking back” their own neighborhood. He had an open call for volunteer portrait subjects — who would hold photographed eyes of local mothers over their own eyes — and he taught the willing participants how to make paste and install the enormous portraits which he enlarged, effectively rallying the community in an art project and humanizing the neighborhood to residents and visitors alike. Distancing himself from the production of his art has become central to JR’s name, which nonetheless brings cache to projects he undertakes. “They started to brainstorm and I just became a witness to the event,” he said. “I’m really just the printer.”

This concept of authenticity and identity most certainly applies to fashion, too. Fashion designers, particularly those with recognizable labels and certainly those in haute couture, have armies of helpers to mold and build any garment. In Valentino: The Last Emperor (an outstanding documentary from 2008), you can observe “the emperor” Valentino loosely sketch a dress and merely tie a bow with fabric on a live model to illustrate how he’d like the embellishment to fall, before handing it over to his head seamstress, the formidable Antonietta de Angelis, who will guide her own team of seamstresses to complete the work. It is these women who must work backwards to create a pattern, cut fabric, stitch together (by hand!), and then present the finished dress to Valentino for critique, whose name will, of course, be the only one on the label.

Some fashion designers are more hands-on, some favor pattern-making or draping themselves, and some even sew garments themselves, but this is by no means the rule. And unless you’re phenomenally naive as an admirer or consumer of such goods, you don’t expect the designer to have done much more than come up with the idea of any given garment. I just finished reading Japanese Fashion Designers: The Work and Influence of Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo (my review here), and the intimate collaboration between fashion designer and textile designer is stressed, yet it is typically the fashion designer alone whose name is recognized by the general public.

Costuming for films has touched upon this theme of credit: you may remember the recent controversy when the influential Mulleavy sisters of Rodarte demanded costume credits for their seven collaborative ensembles in Black Swan (2010), but actually Amy Westcott was the official Costume Designer who oversaw all costume choices (ironically, many movie-goers only recognized the Rodarte label, due to their successful self-promotion). Edith Head was similarly credited with the entirety of the costumes for Sabrina (1954), though now-famous Givenchy provided all Audrey Hepburn‘s stunning gowns.

So I can see why people like David Hockney are dubious of Hirst’s artistic credibility when it seems the dissemination of the artistic process is not actually part of the overarching concept, but instead mere laziness. But money is very much a part of this argument, just as much as fame, or “credit.” People get their knickers in a twist when their concepts of authenticity are challenged, especially if they’re wealthy art / fashion patrons who are presumably throwing around a lot of cash for the satisfaction of not only buying something uniquely spectacular, but something that has retail value and ideally will appreciate in monetary value over time (see my earlier post on collecting). Middle-class consumers are notoriously uninterested in “authentic” artistry, as proven by the rampant fashion knock-off industry.

While some may interpret Hirst’s limited involvement in his own work production as lazy, the complexity of this issue must nevertheless be acknowledged.

3 comments

Tove Hermanson says:

Jul 31, 2013

Thanks, Rachel. You are absolutely right, Renaissance painters worked in “schools.” Even though this was common practice, we still value those “original” or “pure” works by the “master” more, making the challenge of parsing out whose hand was truly involved– no matter how deft the result– and ultimately putting price tags on ambiguously authored works.

Rachel says:

Jul 31, 2013

A very interesting and informative article, thanks. I learned a lot about the fashion design industry that I didn’t know before. Bertrand’s point about ‘process’ and ‘generative’ art is also a good one.

One thing that I didn’t see mentioned here is that, while painting might recently “have a history of being conceived and executed by one person,” that wasn’t the case in the Renaissance, where the norm was for master artists to run their own workshops of assistants and apprentices. The younger artists would spend much of their time learning and practising techniques in order to become masters in their own rights. Depending on the master, they might also contribute to the works that would carry his name (perhaps filling in backgrounds or taking on specialised or more laborious tasks).

Personally I dislike Hirst’s art and tend toward’s Hockney’s assessment of him, but I’m willing to think more about why that is. 🙂

Bertrand says:

May 16, 2012

A very interesting discussion indeed! I would just like to hint at a few of my own thoughts on the subject, although they will certainly lack the depth and variety you display here:

The question of the separation between design, craft and art has obviously spanned over centuries: I wont pretend to bring anything new to the table but I believe that the question of authorship deserves to be examined in the prism of those variations, and I would suggest to look at Wagner in particular: since you mention Warhol for example or Lewitt, I believe both of them insist at one level or the other, that their work is process oriented: the means of it’s own creation is an integral, if not central, part of the artwork itself – in the case of Warhol I see it as the iconic transgression of the separation between high (exclusive) culture and low (mass produced) media, while in Lewitt I see in “generative†artwork an additional level of abstraction upward from Malevitch.

As you say in your conclusion, in those cases the process is subordinate to the concept: that is quite expectable in a contemporary art that places it’s own value increasingly in the intellectual process rather than the material outcome, as Hirst himself acknowledge. Hirst shares with Warhol the complex situation of somewhat embracing captilism, wheras the current zeitgeist leads us to think of art as essentially revendicative, and most likely either marxist or spiritualist, at any rate anti-capitalist in it’s need for an articulated utopian space to situate it’s intellectual constructions. Of course in both cases, they both aim at transgressing the transgression, at denigrating the new statu quo of art as a practice in opposition.

Fashion generally generally focuses it’s experimentations on antagonistic aesthetics, like minimalism, de-construction, post-modernism, etc. Few designers or brands have either the will and the freedom to articulate the conceptuality of their practice like Boudicca does for example. In my opinion this is due to the particular financial status of fashion in general and luxury in particular: the paradoxical “gestaltung†of luxury is informed by the general ignorance of it’s clientele, and yet the need, in order for the designer to secure any form of creative input in what is otherwise a chiefly commercial pursuit, to remain part of the cutting edge fringe of fashion forward and technically perfected luxury designer. In other words, the rich client have the freedom to buy excentric pieces but little understanding of the making itself, which causes most of the costs. But in order for the designer to have the freedom to design excentric clothing the designer needs to maintain the product on the same market level as the rich client. It’s a bit of a vicious circle if you ask me.

My point is that the artist does not need the same investment (if any at all) nor the same financial pressure as the designer does. Taking a simple look at the history of the Turner Prize for example, shows how little investment can make a work that is considered pivotal. One could even be tempted to think of art as chiefly defined (in an indulgently bohemian outlook I admit) by it’s accessibility: when a piece requires technological or financial means to be produced, it becomes the exception, and, like Warhol and Lewitt, by stepping out of the “minimumâ€, the process become part of the artwork.

So in the end I would be tempted to think that wheras the fact that the financial means involved in, for example, those diamond skulls that illuminate the Tate Gallery at the moment, can be considered as a form of process art (and in that regard constitue a sort of counter-counter-narrative, that could be of interest to some), I don’t see how the sea of nameless assistants, and of unpaid interns, that one can picture as taking part in the dot painting process, fit with the character of Hirst’s work: it has been done before, it is not even highlighted or integrated in any form of narrative. If he was to make an artwork featuring the slavery of his assistants as a central theme I would smile and cheer, but in the present case I am inclined to think it is nothing more than a tool.