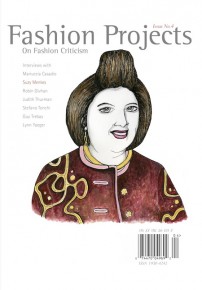

On Fashion CriticismFrancesca Granata, EditorFashion Projects (Issue #4, February 2013)

Fashion Projects, a non-profit magazine devoted to fashion theory and reflection, has come out with an issue on fashion criticism itself (available in print, with select sections online), screened through interviews with some of the most well-known and well-respected names in the field, including Robin Givhan, Guy Trebay, Judith Thurman, and Suzy Menkes. In her introduction, Editor Francesca Granata suggests fashion journalism is at a crossroads, teetering on the brink of “legitimation.†She rightly questions the time it has taken for fashion to be considered a serious scholarly pursuit, and how it still needs to justify itself as a cultural indicator, as photography, music, and film scholarship have attained decades ago. Also discussed is the relationship between fashion and art; the role technology has played in disseminating fashion images and commentary, and the effects this has had on fashion production; and how printed versus image-driven new media continues to influence fashion criticism. Interview subjects came from a plethora of intellectual and professional backgrounds, only eventually arriving at fashion criticism. Like me, they inevitably studied other disciplines— a foundation in the arts and humanities seems to have shaped the distinctly sociological, cultural, and interdisciplinary methods of analysis taken for granted in fine arts and literature to inform these influential careers in fashion journalism.

DIVERSITY OF EXPERIENCE

Journalist Robin Givhan rather accidentally began writing about fashion in one of her first jobs, couched under the general “entertainment†section. Similarly, Guy Trebay of the New York Times initially wrote about music, the crack epidemic, and “urban anthropology” of New York City for the Village Voice. Freelance fashion critic Lynn Yaeger worked in the advertising department for her first 15 years at the Village Voice, before another 15 years writing their fashion columns; and Judith Thurman eventually came to write about fashion for the New Yorker as an extension of her writings on femininity and “women’s work.”

For Thurman, fashion is “an important element of culture and is itself a culture…. It is a form of expression, a kind of language dealing with identities.â€

Before launching T Magazine of the New York Times and becoming the current Editor-in-Chief of W magazine, Stefano Tonchi addressed the intersection of art, architecture, and design. He contends that his work as an exhibition curator honed his selection and editing skills, also essential for meaningful “transdisciplinary” fashion writing. Another Italian critic, currently with Vogue Italia,Mariuccia Casadio also comments on fashion, art, design, and architecture, all of which she studied at DAMS (Disciplines of Arts, Music and Spectacle) in Bologna. Like Tonchi, her interest in fashion grew out of her curatorial work and writings on art. Far from a coincidence, the fields these respected fashion critics emerged from—architecture, design, advertising, fine art, and entertainment—already acknowledged and addressed the connection between visual arts and culture.

FASHION AS CULTURAL TOUCHSTONE

Robin Givhan gave hope to fashion scholars everywhere after she won a Pulitzer Prize for fashion criticism while writing for the Washington Post. But this was hard-won recognition, and not necessarily a win for the discipline at large; the Pulitzer justification that Givhan’s articles “transform fashion criticism into cultural criticism†denies the existence of substantial fashion criticism as a field by making her approach seem, not simply exemplary, but entirely unique. Givhan observes that yes, some fashion writers choose to view fashion merely as colors, hemlines, and textures, but others (like herself) concentrate on “the importance that our culture places on public presentation and the way that it is woven into our economics, politics, religion, social hierarchy….†She suggests that the fashion industry itself often ignores or subverts the cultural implications of dress in favor of the more superficial trends.

Meanwhile, the interviewees in Fashion Projects challenge this surface approach to style. Suzy Menkes, fashion editor for the International Herald Tribune and recipient of the Order of the British Empire for “services to fashion journalism,†defines her interest in apparel as distinctly cultural: “clothes mirror what is happening in the world—and fashion often tells you in advance.†Yaeger remembered finding her voice in fashion journalism, taking cues from film and cultural criticism: “I admired writing that was left-wing, that had sort of a political critique and a historical critique to culture.†Tonchi sees this socio-cultural approach gaining acceptance:

“It is very interesting how we are looking in a very deep way and thinking deeply about something that is very ‘superficial’ [like fashion]. It is better than what happened in the 1970s, when everybody was superficially studying very deep subjects like human interactions or politics.â€

A FEMININE PURSUIT?

Tonchi suggests that “fashion as a cultural form†has already been established in France, as the birthplace of haute couture, but not in Italy or America where fashion’s connection to industry is seen as a contradiction prohibitive to meaningful analysis (see how his art background came through there?). Thurman (who also lived in Europe) agrees that America has a particularly contentious relationship with fashion, but she attributes it to America’s Puritan roots, owing to “the [feminine] Eros of fashion and the relation between fashion and sex.†Trebay explicitly sited sexism as a hurdle in gaining respect and recognition in his field, “having to rehabilitate things that are considered culturally beneath regard… without sacrificing what’s beautiful and delightful about the ephemeral and frivolous part of it. Those are not opposing ideas.†He attributes much of this degradation of fashion to its feminine connotations, but also to being “hijacked by the visuals,†an increasing struggle with the convenience and speed of digital imagery.

IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGY

All the critics in this volume established their careers before the internet — though many of them publish online now — and all had strong opinions about the how the technology has affected their practice. Like Trebay,

Casadio admits the proliferation of fashion images on the internet “are a fundamental dimension of the fashion discourse but I start feeling that this extreme proliferation is taking away some power from the image…. I want to recall the magical power of the word.â€

Menkes cautions armchair fashion bloggers that fabric and color details cannot be communicated effectively through digital representation. Trebay discussed the inadequacy of online sources for runway critique because the sociology of human interactions at the shows is “a little more opaque online, which is more garment-based.†Givhan expressed concern that as fashion writing moves away from general-interest newspapers and increasingly appears in industry magazines and fashion-specific blogs, that it actually becomes more insular and less democratic — even as knock-offs can be purchased cheaply at down-market venues due to wider and faster dissemination of runway fashions and street styles. Yaeger claimed intellectually and politically she appreciates the added voices of fashion critic bloggers —“the more people that see the collections, the less elitist it becomesâ€â€”though it is daunting to be diluted by less experienced writers. While fashion bloggers offer diverse perspectives, Menkes finds intelligent, articulate and illuminating commentary “rare.†Similarly double-edged, increased publicity of red carpet style garners deserved attention to fashion and contemporary designers, but Thurman and Givhan point out this perpetuates fashion as an extension of celebrity obsession, and not necessarily as a thoughtful socio-cultural expression.

A “mah-velous” example of technology used to great effect in fashion reporting seems to be the New York Times’ fashion photographer Bill Cunningham, who has a profile in this Fashion Projects. An unlikely candidate for mastering an online presence, Cunningham, in his 80s, nonetheless delivers a delightful voice-overed romp through his themed weekly street photos to accompany his pictoral column “On the Street.†In the awesome documentary Bill Cunningham New York (2010), you can see for yourself the meticulous nit-picking Cunningham engages in with his layout man, versus the one-shot stream-of-consciousness technique he employs to record the audio file about those same photos, illuminating the theme he has selected and enhancing his product in the process. Menkes encourages technological tools that facilitate the circulation of interviews, new fashion developments, and dialogs between artists and their audiences — I believe Cunningham’s voice-overs satisfy this criteria with aplomb.

Though I’m afraid it reveals some of my own schadenfreude, I was frankly heartened to learn that nearly all these accomplished veterans of fashion journalism expressed difficulty in writing. Thurman was candid in her struggles to write meaningfully and artfully. Casadio, also, is open about the challenge of actually putting words down:

“Writing is a painful process. I love the word, I love to think about fashion in words. When I start to process these two things together, I sink deeply into a latrine of desperation, in a constant research of perfection. I’m bleeding.”

Additionally, Casadio suggests that there may be a baseline vocabulary deficiency which hinders a greater fashion critical discourse (I’m not sure I concur, but it’s an interesting thought). Significantly, many of these subjects excluded the word “fashion” from defining their work: Menkes prefers the generic “reporter” to “fashion critic;” Trebay defines himself as a “cultural critic.” I wonder if, in our effort to communicate how broad and interdisciplinary fashion is, we are not doing our field a disservice by excluding it from our titles (I myself like “Fashion Culturalist”)? Unlike other disciplines, including fine art, all people participate in fashion, and, to varying degrees, we all become adept at expressing (or concealing) profession, age, gender, ethnicity, etc., and learn to read these complicated signals in others, probably inadvertently; fashion is therefore simultaneously universal and highly personal. It is the job of the fashion critic — whatever we may call ourselves — to interpret and elucidate these complicated signs and symbols. Though the golden age of printed publications is waning, the current generation of fashion critics are lucky that we have such technologies to research, photograph, and self-publish glorious combinations of words, written and audible; images, moving and still; and to disseminate our particular brand of fashion critique. Armed with these tools, and our own diverse backgrounds, we can build on the transdisciplinary approaches of these mentors, until “fashion” carries the gravitas of “current events,” as it should.

Book Review: On Fashion Criticism

by Tove Hermanson on Feb 27, 2013 • 10:20 am No Comments

On Fashion Criticism Francesca Granata, Editor Fashion Projects (Issue #4, February 2013)Fashion Projects, a non-profit magazine devoted to fashion theory and reflection, has come out with an issue on fashion criticism itself (available in print, with select sections online), screened through interviews with some of the most well-known and well-respected names in the field, including Robin Givhan, Guy Trebay, Judith Thurman, and Suzy Menkes. In her introduction, Editor Francesca Granata suggests fashion journalism is at a crossroads, teetering on the brink of “legitimation.†She rightly questions the time it has taken for fashion to be considered a serious scholarly pursuit, and how it still needs to justify itself as a cultural indicator, as photography, music, and film scholarship have attained decades ago. Also discussed is the relationship between fashion and art; the role technology has played in disseminating fashion images and commentary, and the effects this has had on fashion production; and how printed versus image-driven new media continues to influence fashion criticism. Interview subjects came from a plethora of intellectual and professional backgrounds, only eventually arriving at fashion criticism. Like me, they inevitably studied other disciplines— a foundation in the arts and humanities seems to have shaped the distinctly sociological, cultural, and interdisciplinary methods of analysis taken for granted in fine arts and literature to inform these influential careers in fashion journalism.

DIVERSITY OF EXPERIENCE

Journalist Robin Givhan rather accidentally began writing about fashion in one of her first jobs, couched under the general “entertainment†section. Similarly, Guy Trebay of the New York Times initially wrote about music, the crack epidemic, and “urban anthropology” of New York City for the Village Voice. Freelance fashion critic Lynn Yaeger worked in the advertising department for her first 15 years at the Village Voice, before another 15 years writing their fashion columns; and Judith Thurman eventually came to write about fashion for the New Yorker as an extension of her writings on femininity and “women’s work.”

Before launching T Magazine of the New York Times and becoming the current Editor-in-Chief of W magazine, Stefano Tonchi addressed the intersection of art, architecture, and design. He contends that his work as an exhibition curator honed his selection and editing skills, also essential for meaningful “transdisciplinary” fashion writing. Another Italian critic, currently with Vogue Italia, Mariuccia Casadio also comments on fashion, art, design, and architecture, all of which she studied at DAMS (Disciplines of Arts, Music and Spectacle) in Bologna. Like Tonchi, her interest in fashion grew out of her curatorial work and writings on art. Far from a coincidence, the fields these respected fashion critics emerged from—architecture, design, advertising, fine art, and entertainment—already acknowledged and addressed the connection between visual arts and culture.

FASHION AS CULTURAL TOUCHSTONE

Robin Givhan gave hope to fashion scholars everywhere after she won a Pulitzer Prize for fashion criticism while writing for the Washington Post. But this was hard-won recognition, and not necessarily a win for the discipline at large; the Pulitzer justification that Givhan’s articles “transform fashion criticism into cultural criticism†denies the existence of substantial fashion criticism as a field by making her approach seem, not simply exemplary, but entirely unique. Givhan observes that yes, some fashion writers choose to view fashion merely as colors, hemlines, and textures, but others (like herself) concentrate on “the importance that our culture places on public presentation and the way that it is woven into our economics, politics, religion, social hierarchy….†She suggests that the fashion industry itself often ignores or subverts the cultural implications of dress in favor of the more superficial trends.

Meanwhile, the interviewees in Fashion Projects challenge this surface approach to style. Suzy Menkes, fashion editor for the International Herald Tribune and recipient of the Order of the British Empire for “services to fashion journalism,†defines her interest in apparel as distinctly cultural: “clothes mirror what is happening in the world—and fashion often tells you in advance.†Yaeger remembered finding her voice in fashion journalism, taking cues from film and cultural criticism: “I admired writing that was left-wing, that had sort of a political critique and a historical critique to culture.†Tonchi sees this socio-cultural approach gaining acceptance:

A FEMININE PURSUIT?

Tonchi suggests that “fashion as a cultural form†has already been established in France, as the birthplace of haute couture, but not in Italy or America where fashion’s connection to industry is seen as a contradiction prohibitive to meaningful analysis (see how his art background came through there?). Thurman (who also lived in Europe) agrees that America has a particularly contentious relationship with fashion, but she attributes it to America’s Puritan roots, owing to “the [feminine] Eros of fashion and the relation between fashion and sex.†Trebay explicitly sited sexism as a hurdle in gaining respect and recognition in his field, “having to rehabilitate things that are considered culturally beneath regard… without sacrificing what’s beautiful and delightful about the ephemeral and frivolous part of it. Those are not opposing ideas.†He attributes much of this degradation of fashion to its feminine connotations, but also to being “hijacked by the visuals,†an increasing struggle with the convenience and speed of digital imagery.

IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGY

All the critics in this volume established their careers before the internet — though many of them publish online now — and all had strong opinions about the how the technology has affected their practice. Like Trebay,

Menkes cautions armchair fashion bloggers that fabric and color details cannot be communicated effectively through digital representation. Trebay discussed the inadequacy of online sources for runway critique because the sociology of human interactions at the shows is “a little more opaque online, which is more garment-based.†Givhan expressed concern that as fashion writing moves away from general-interest newspapers and increasingly appears in industry magazines and fashion-specific blogs, that it actually becomes more insular and less democratic — even as knock-offs can be purchased cheaply at down-market venues due to wider and faster dissemination of runway fashions and street styles. Yaeger claimed intellectually and politically she appreciates the added voices of fashion critic bloggers —“the more people that see the collections, the less elitist it becomesâ€â€”though it is daunting to be diluted by less experienced writers. While fashion bloggers offer diverse perspectives, Menkes finds intelligent, articulate and illuminating commentary “rare.†Similarly double-edged, increased publicity of red carpet style garners deserved attention to fashion and contemporary designers, but Thurman and Givhan point out this perpetuates fashion as an extension of celebrity obsession, and not necessarily as a thoughtful socio-cultural expression.

A “mah-velous” example of technology used to great effect in fashion reporting seems to be the New York Times’ fashion photographer Bill Cunningham, who has a profile in this Fashion Projects. An unlikely candidate for mastering an online presence, Cunningham, in his 80s, nonetheless delivers a delightful voice-overed romp through his themed weekly street photos to accompany his pictoral column “On the Street.†In the awesome documentary Bill Cunningham New York (2010), you can see for yourself the meticulous nit-picking Cunningham engages in with his layout man, versus the one-shot stream-of-consciousness technique he employs to record the audio file about those same photos, illuminating the theme he has selected and enhancing his product in the process. Menkes encourages technological tools that facilitate the circulation of interviews, new fashion developments, and dialogs between artists and their audiences — I believe Cunningham’s voice-overs satisfy this criteria with aplomb.

Though I’m afraid it reveals some of my own schadenfreude, I was frankly heartened to learn that nearly all these accomplished veterans of fashion journalism expressed difficulty in writing. Thurman was candid in her struggles to write meaningfully and artfully. Casadio, also, is open about the challenge of actually putting words down:

Additionally, Casadio suggests that there may be a baseline vocabulary deficiency which hinders a greater fashion critical discourse (I’m not sure I concur, but it’s an interesting thought). Significantly, many of these subjects excluded the word “fashion” from defining their work: Menkes prefers the generic “reporter” to “fashion critic;” Trebay defines himself as a “cultural critic.” I wonder if, in our effort to communicate how broad and interdisciplinary fashion is, we are not doing our field a disservice by excluding it from our titles (I myself like “Fashion Culturalist”)? Unlike other disciplines, including fine art, all people participate in fashion, and, to varying degrees, we all become adept at expressing (or concealing) profession, age, gender, ethnicity, etc., and learn to read these complicated signals in others, probably inadvertently; fashion is therefore simultaneously universal and highly personal. It is the job of the fashion critic — whatever we may call ourselves — to interpret and elucidate these complicated signs and symbols. Though the golden age of printed publications is waning, the current generation of fashion critics are lucky that we have such technologies to research, photograph, and self-publish glorious combinations of words, written and audible; images, moving and still; and to disseminate our particular brand of fashion critique. Armed with these tools, and our own diverse backgrounds, we can build on the transdisciplinary approaches of these mentors, until “fashion” carries the gravitas of “current events,” as it should.

You May Also Enjoy: