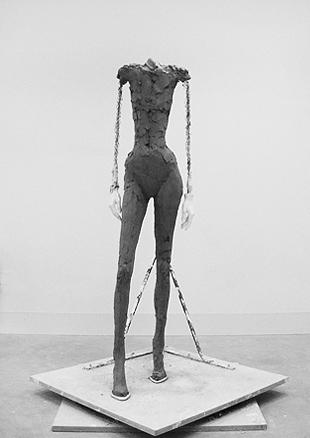

The recent announcement of MoMA’s website devoted to Louise Bourgeois: The Complete Prints & Books, got me thinking about insects. I adore Ms. Bourgeois’ sculptures and installations, and her continued use of spider imagery over her long career (she died at age 98 in 2010) to explore issues of the feminine experience never ceased to astonish and touch me with their haunting beauty. She returned to the spider over and over again, as in her Maman series about her mother, encompassing “metaphors of spinning, weaving, nurture and protection” (see my previous posts about Domestic Sewing Traditions for more on these themes). Her spiders, most of which are so large as to loom over people and compete for sky space with adjacent buildings, often appear to be coiled out of great ropes of spun metal, emanating pliable strength. In her Cell series, Bourgeois incorporates actual fiber textiles into dimly lit, intimate settings that evoke solitary labors of generations of women toiling on sewing / knitting / mending projects to clothe and furnish their households.

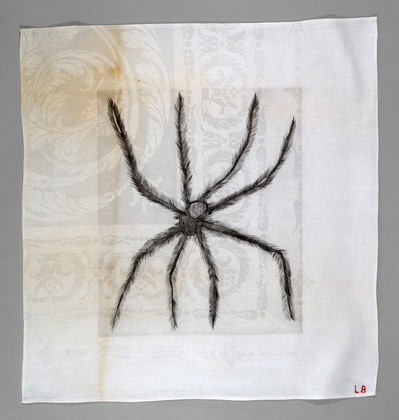

Bourgeois not only incorporated textiles into her installations, she also produced works on fabric, such as this “Hairy Spider,” drypoint-printed on what appears to be a tablecloth or napkin, linking the material to a specific domestic, food-oriented object frequently associated with women and their role as nurturing feeders:

Much as Bourgeois used variations of the spider in her work, Sarah Burton’s Spring / Summer 2013 collection for Alexander McQueen used bee imagery to address an endless stream of concepts in materiality, sex and mortality, all in typically sumptuous textiles of unusual textures and daring silhouettes. Burton seems to have created crustacean-like exoskeletons with this collection, from the structured tailoring to the faux tortoise shell accessories, borrowing another animal’s protective armor.

Like spiders, bees are builders, and variations of geometric motifs abounded, especially the hexagon of bee hives and its beautiful combination of structure and transparency (the latter of which has been all the rage in recent years and which I’m frankly mostly tired of). In the following example, the McQueen cutoff jacket, sharp wasp-waist (ha!), and rounded hips further mimic a bee’s sectional armor. I especially enjoy the mottled gold-and-black netting skirt which looks simultaneously like a work in progress or as though it’s decaying, gold-to-black or black-to-gold.

It got me thinking about the peculiar contradictions of transparency, the relationship between empty holes and the inverse strength from surrounding structure, and how humans have devised our own highly structured, open-faced cages ranging from hoop skirts to buildings. Profoundly modern in so many aspects of her fashion collections, Burton was nonetheless making the same historical connections I was, hearkening back to other fashion objects that relied upon structured grids, namely lace and the hoop skirt:

In stark contrast to their industriousness, in art and fashion insects have typically been symbols of abbreviated lifespans, harbingers of plague, and therefore mortality, as in this 17th century still life which has blooming flowers (symbolic of life)…

…but in the detail you can see the spider the and (dead) wasp, reminding the viewer of life’s brief cycle:

Eccentric Surrealist fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli (1890–1973) loved incorporating insects into her clothes and jewelry. Though Surrealism is frequently interpreted as nothing more than light-hearted whimsy and puns, this is only partially accurate. Having been most active during the economically depressed and politically tumultuous 1930s, between the Spanish Civil War and WWI, deterioration, mutilation, and death pervaded everyday living, and the Surrealists reflected on this with jarring, disjointed collages, eerie dreamscapes, and yes, insects. Schiaparelli referenced the still life oeuvre with her enameled leaf necklace in which hides a cricket among the dying leaves (far left), and her highly realistic cricket buttons:

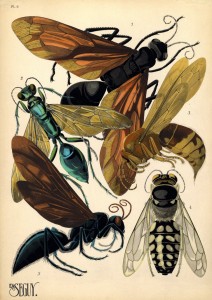

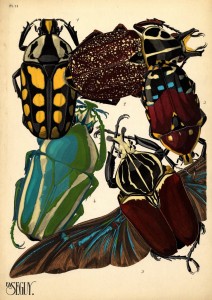

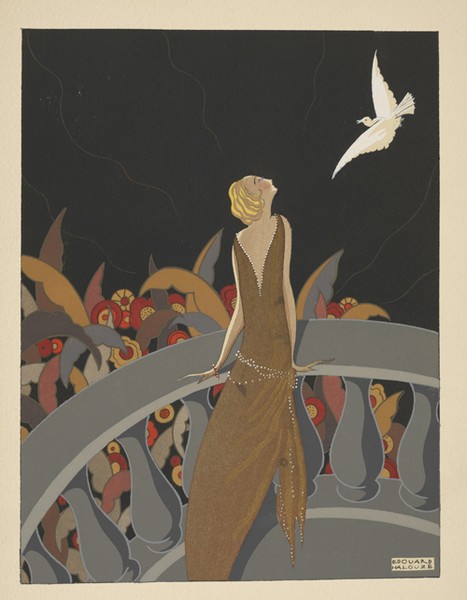

Her more famous insect necklace seems to be more humorous, with comically colorful plastic bugs seemingly crawling around the wearer’s neck, but they also resemble the painstakingly accurate sketches of entomologist / artist Eugène Séguy (1889 – 2012), who utilized the pochoir technique on paper and textiles to create stunningly vivid, stylized compositions of the insect world in the early decades of the 20th century (following the Art Nouveau obsession with more traditionally beautiful flora and fauna):

My good friend Mielle Harvey is a phenomenally talented jewelry designer whose Hexapoda line of “art jewelry” almost exclusively depicts insects: moths, bees, and my personal favorite, beetles. The rough texture of many of her pieces compliments the cycles of rebirth and decay she’s interested in. Her artist statement sums it up:

“I use art to emotionally express the tension I feel between life, mortality and the fragility of existence. Across each artistic medium, nature, with its beauty and harsh realities, provides the inspiration for my work. By combining elements and sometimes materials which both attract and repulse, I aim to challenge the viewer to question the traditional values associated with beauty and adornment.â€

Of the pieces my partner has lovingly commissioned from Ms. Harvey for me, here are two of my favorites: my beetle engagement ring; and my latest acquisition, a spider necklace (with caught fly and two cocoons) on “deteriorating” crocheted silk thread:

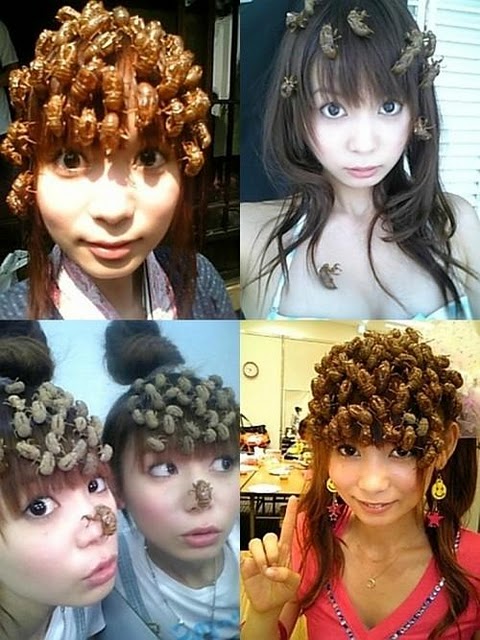

To peruse other beautiful creepy-crawly objects, check out the many wonderful Pinterest boards with that description. And if you fancy something buggy that’s a little more extreme, check out the Japanese entertainer Shokotan, who has taken to wearing live cicadas on her head in a kind of helmet. You’re welcome very much.