After seeing Gisele Bundchen’s latest Vogue shoot entitled “Call of Duty” in various military-inspired ensembles, my conflicted feelings about the sexifying of war gear swung hard and fast in the “that’s not cool” direction. Huffington Post presents these images with significantly less conflict: “let us know which is Gisele’s fiercest moment.” I should mention that this was shot for Vogue Korea no less — presumably South Korea, but a country locked in heated, no-end-in-sight military animosity with its former countrymen. (Insular, distinctly militaristic North Korea now has the highest percentage of military personnel per capita of any nation in the world with approximately 1 enlisted soldier for every 25 citizens.) I mean, I wonder if anyone involved in this Vogue fashion shoot experienced any irony whatsoever. Photographed by Nino Muñoz, clothes are from Balmain, Alexander Wang, Chloé and others in Call of Duty (in case you didn’t get the soldier reference from the images alone). Some choice selections follow.

In Vogue Korea of May 2010, Gisele is so parched from her desert swim that she must provocatively douse herself with her canteen;Â the practical cargo shorts paired with the distinctly impractical shorty army-issued t-shirt and stiletto-heeled combat booties are almost laughable;Â one has clean lines and uniform (as opposed to combat) tailoring that generally appeal to me, but it’s still disturbingly devoid of irony or socio-political critique.

Now, shall we look at some historical moments when military uniforms crossed over into day wear? Frederick Law Olmsted (1822 – 1903) noted that after the Mexican War (1846 – 48) “a great deal of military clothing was sold at auction in New Orleans, and much of it was bought by planters at a low price, and given to their negroes, who were greatly pleased with it.” Not only did military uniforms carry the associations of literal warfare, but they had the compounded layer of becoming sloppy seconds for African American slaves. Later, the surplus army clothing of the Civil War (1861 – 65) was adopted by Western frontiersmen: functional heavy coats and trousers, double-breasted pullover shirts, boots, and individually crimped hats were appealing to those living a rugged civilian lifestyle. And many men who served in WWII found many articles of clothing designed for warfare (i.e. khaki pants) to be comfortable, practical, and even stylish. War generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, George Patton, and Douglas MacArthur became fashion icons of sorts, and the sensible “Eisenhower jacket” was adopted by men and women for its formal practicality:

In the years immediately following WWII, record numbers of veterans entered colleges (in 1946, 75% of entering Harvard students were former G.I.s), bringing with them the comfortable and practical khaki pants, fitted tailored shirts, and casual military jackets. With America’s current casual collegiate styles this might not seem noteworthy, but pre-WWII college students typically dressed in suits and ties, emulating the businessmen many aspired to become, and the casual military look was a sharp digression.

But the natural dissemination of actual army/navy clothes into regular society is a far cry from the fashion industry appropriating military as a trendy look (see Style.com “Marching Orders” trend). In one aberrant season of Rudi Gernreich (1922-1985), better known for his whimsical ’60s graphic mini dresses and topless swimsuit, his 1970 resort collection was distinctly military inspired. His muse and model Peggy Moffitt actually brandished a rifle in a different shot, as did the models on the live runway (and this is one of the tamer looks):

Generally embracing a mod-meets-hippie look, Gernreich showed this controversial collection just months after the Kent State shootings and during the dragging Vietnam War (1955 – 75). During a 1985 retrospective presentation at the Smithsonian Institute, Gernreich commented, “I did the military look in the late 1960s because some designers were making Scarlett O’Hara clothes, which I thought was an insult to women when they were becoming totally equal to men.” I’m the first to admit military-influenced styles of WWII acted as a gender equalizer (see my other posts on War), but Gernreich’s feminist message was lost and this is an inherent problem with glorifying military clothes: there is too much damn violence in the world for it ever to be appropriate without implied commentary (making it shorter/tighter/sexier does not count unless you’re trying to say “war is sexy”).

On the one hand, I have residual fondness for pairing fancy bling with camo — I think it can call attention to the inherent disconnect between wealth, individuality, style, and the conforming, functional purpose of military uniforms that are mostly worn by the young, underprivileged, and uneducated racial minorities. On the other hand, glamorizing the military — especially when one’s own country is in a dragging, controversial war — seems problematic. As a designer (or a photographer, or a model), how do you make this distinction? I am all about playful fun in fashion, but glamorizing bigotry and government-sanctioned violence is distasteful at best and irresponsible at worst. Practical innovations that have come from military issued uniforms should absolutely be adopted by the general public: deep cargo pockets and trench coats are utilitarian and stylish. But making sexually provocative military clothes is not conceptually provocative.

There is some interesting art incorporating fashion and the military. Peter Gronquist’s show entitled “Firearms and Fashion” included weapon objets d’artes with fashion house labels, alluding to a complicit (if vague) relationship between corporate fashion and violence. Below is a Burberry rifle from the collection:

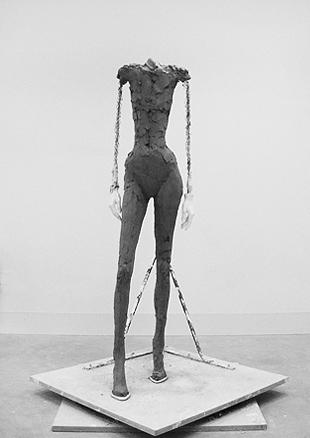

Bringing back the Korean military thread, I saw a powerful piece last summer of Do-Ho Suh’s entitled “Uni-Forms: Self-Portrait/s: My 39 Years” from 2006:

This is a sartorial timeline of Suh’s mandatory life in the South Korean army, from the disturbingly tiny boy’s crested jacket to the full-grown man’s camo and khakis.

Martha Rosler is known for collaging images of the Vietnam battlefield and magazine clippings from the home front including fashion models, washing machines, living room sofas, Playboy nudes, etc. Here is a more recent 2006 work using Iraqi/Afghani footage with a superimposed fashion model who appears to be turning away from the confrontation:

Though the model doesn’t actually wear military gear, it does point to an irresponsible relationship between the fashion world (and the public that so eagerly consumes it) and concurrent warfare.

So readers, do you think it’s ever ok to sexify military wear, and if so, in what context?

Further Reading:

- NYTimes article on “Houlihan” M*A*S*H cargo pants (especially funny, since M*A*S*H was a deeply anti-war film and TV series)

- Precision Targets and the Militarization of Everyday Life from Threadbared

4 comments

Jayn says:

Jun 7, 2010

I think it already started in WWII when the military in America recruited women for the WAC, WAVES, SPARS, WASP etc.! Recruitment campaigns tried to convince as many women as possible with posters, brochures, newspaper advertisements and even movies to join these services. Often they promoted an unrealistic, glamorous and in a way sexualized image of the female army member with a Hollywood-star make-up and style! In these times clothes, fabrics and make-up were rationed and the supplies where scarce. The army had the WAVES and SPARS uniform designed by a french designer to make it more appealing and this did attract recruits. The waves were considered the best-dressed women in america! Joining the army also meant that a woman was able to save money for other beauty items because she did not spend money on civilian clothes. In WWII Joining the armed forces meant new perspectives and possibilities especially for poorer women and it was also one step further to equal rights. Nevertheless these images paved the way for the further fetishizing of military gear like today!

Megan says:

May 28, 2010

I wouldn’t go so far as to say that the Gisele shoot is without commentary. It’s not insightful commentary, and it’s not in line with your more pacifist views. But isn’t propaganda its own form of commentary, lazy and shallow though it may be?

Tamara Spiegel says:

May 26, 2010

I’m all for a good cargo short, epaulet jacket, combat boot or cross-body bag, but such literal styling of military-inspired fashion definitely misses the point. Part of fashion is taking very didactic themes and making them work in a new context. When most of these pieces were shown on the runways, they were part of genre mixes that acknowledged the campiness and irony of it all–Burberry paired canvas army belts with frothy little dresses, Balmain with ridiculous over-the-top sparkles and distressing, and countless others adapted fatigue greens into silks, cargo pockets into feminine dresses. As someone in the business of trend forecasting, I can’t blame volume companies for wanting to maximize on a such a mainstream-accessible concept–Hollywood has been romanticizing war for decades. But the styling and direction of this Vogue shoot looks like college girls on Halloween trying to do “sexy soldier” or a pinup magazine for GIs to hang in their bunks. They’ve taken some great high-fashion military inspired pieces, stripped them of their irony and essentially degraded them into bad costume.

Matt Katz says:

May 25, 2010

It’s very disturbing – without the wink or the nudge this looks like a glamorization of the military, which is like the police. The people in it are mainly good, some are very bad, and it would be a better world if we didn’t require their services.