Though I love me some fashion, I confess I do not keep up with every single fashion collection that graces the runways (is it even possible, I sometimes wonder?). However, I happened to catch Dior’s Fall 09 collection recently and fell in love — both in the playful I-want-to-wear-that way and also the that-epitomizes-such-an-interesting-historical-trend way, leading to the inevitable I-must-blog-about-that-now conclusion. And so here we are.

For the couture Fall 09 collection of the Christian Dior label, designer John Galliano has played with the staples of ’50s innerwear and supporting garments by revealing them, eliminating portions of the outerwear and exposing the skeleton of what actually creates those feminine curves a la Dior’s own post WWII “New Look.†Galliano admitted that he’d been inspired by photos of Dior himself dressing his models before one of his salon shows in the 1950s. Galliano took the state of semi-dress and moved it from behind the curtain to in front of it, going one step further in his homage by presenting his 2009 collection in an intimate salon-esque setting rather than the modern blockbuster runway format. Here are a couple of my favorite items from the series:

The skirt is pared down to the stiff, transparent structural garment necessary to create the “naturally” feminine looks of the 1950s.

This has a modest silhouette but is obviously completely gauzy, ironically revealing “proper” 1950s understructures.

Let’s take a closer look at the fashions of the mid-20th century from which Galliano derived inspiration, shall we?

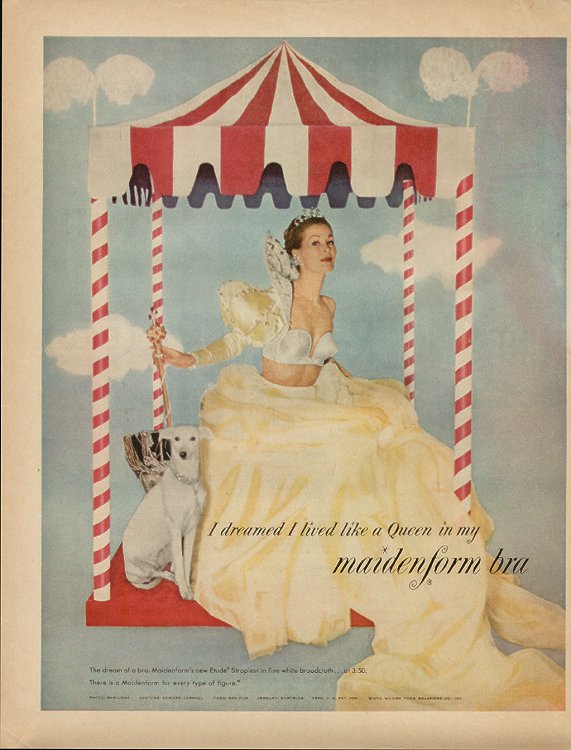

A tremendously successful Maidenform bra ad campaign in the ’50s and ’60s featured models in ordinary situations, dressed traditionally from the waist down, but swathed only in Maidenform bras above the waist.

It’s incredible how like Dior’s collection these ads are, non?

World War II necessitated rationing of all kinds: gasoline, metal, fabric, chemical dyes, and more. When the war concluded, droves of young military men returned to the States, hungry for women in all their stereotypically soft, curvy, feminine glory. Post-war women wanted to mimic glamorous actresses they’d been seeing in escapist movies all along, to replace the utilitarian suits and pencil skirts they’d adopted out of patriotic wartime necessity. Fashion responded to these desires and took advantage of the lifted restrictions to create voluminous skirts with yards of fabric, cinched waists and uplifted, pointy breasts to exaggerate the idealized curvy feminine body. And, as always, structural undergarments had tremendous import in realizing that ever-morphing, ever-exaggerated, idealized shape.

Undergarment retailers capitalized on the lifted restrictions by experimenting with color, sheer fabrics, lace and printed patterns, new fabrics like Dacron, nylon, Spandex, and rayon. These synthetic materials (several originating in government and military labs) provided durable, stretchy, lightweight alternatives to stiffer, heavier undergarments made of natural fibers like cotton and linen which needed boning for support, shape, and structure. Pantyhose were introduced in 1959, combining panties and “hose†or stockings, a mini revolution in underwear. Stockings even as late as the early 20th century were not terribly stretchy. Romanticized today (not least of all by Yours Truly), the pesky back seams had to be manually straightened and their leg shapes were predetermined. So if your legs didn’t conform, you were left with distinctly un-sexy, ill-fitting stockings with loose knees and saggy fabric wrinkles:

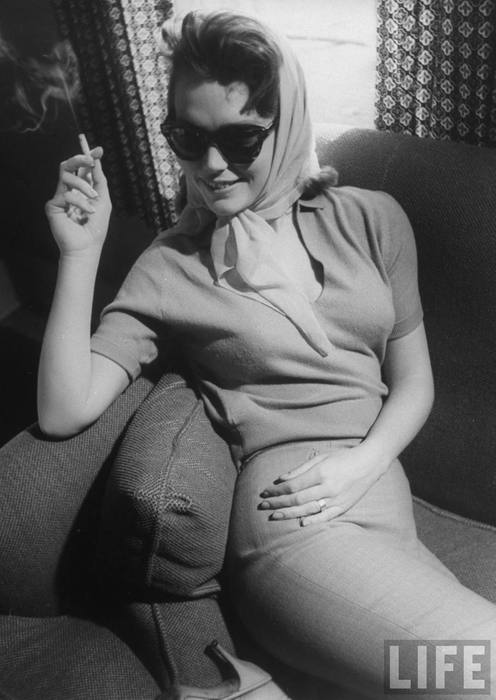

In the late 1940s, designers like Jacques Fath incorporated corset lacings into evening wear, a risqué reference that also reflected the fashion for hourglass figures and the return of conventional notions of femininity post-WWII. While the glamorous films of the ’40s (which generally depicted wealthy society folk whose extravagant lifestyles were left suspiciously unaffected by the war raging in the real world) were the inspiration in the early 1950s, films of that mid-century decade placed their own indelible stamp upon the collective fashion ideals, shifting the trends from genteel aristocrat to slightly bawdy Everyman (or Everywoman as the case often was), creeping toward the sexual revolution of the 1960s. Marilyn Monroe simultaneously shocked and delighted audiences by going braless on and off sets, a kind of prelude to the feminist-organized bra burning episodes of the ’60s without the overt politics. Elizabeth Taylor wore a custom made slip for much of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), and the sizzling posters of her call girl character in BUtterfield 8 (1960) depicted her with a heavy fur coat draped over her body-hugging slip, heightening the impact of her near-nakedness:

Galliano similarly pairs outdoor coats with slips:

In Anatomy of a Murder (1959) attorney James Stewart is forced to request his client’s wife wear a girdle in court to make her appear respectable and decent — though he admits with embarrassment that the young woman doesn’t need one to control her “jiggle†(more to the audience’s discomfort than to the precocious sex kitten character to whom he is speaking).

AFTER: Lee Remick deliberately dowdy in courtroom in Anatomy of a Murder. Though unseen, she presumably wears a girdle under her tweed skirt.

Here we see the girdle on the model, who, like Lee Resnick above, does not actually require such a supportive garment to mold her shape:

In Rear Window (1954), Costume Designer Edith Head ensconces Grace Kelly’s socialite character in a dress of layered tulle, a transparent material that is traditionally used as an underlayer to provide volume to outerskirts. While this dress hardly screams “vulgar,” it’s definitely a wee bit risqué. The see-through wrap Grace Kelly dangles is just one layer of the same material used for her skirt, typifying the deliberately impractical, beautiful glamour popular post-WWII (a transparent wrap not only doesn’t assist modesty, it doesn’t shield from the cold either).

And here is a Dior creation:

This skirt has fewer layers of tulle than the example above, drawing attention to the sheerness of the material which is more commonly used in lingerie.

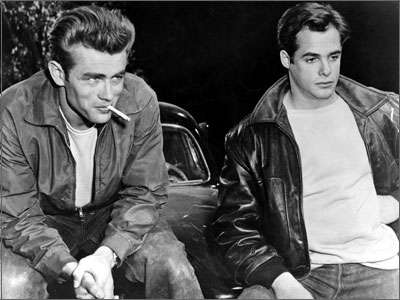

The steamy Streetcar Named Desire (1951) is set in humid New Orleans where characters languor in states of semi-dress. In a poignant-though-subtle twist, Kim Hunter’s ferociously monogamous character Stella walks around the apartment in a slip, in stark contrast to the false prudery of Vivien Leigh’s Blanche DuBois whose extreme, inconvenient modesty (three adults are living in a tiny one bedroom apartment) belies her previous promiscuity. Marlon Brando’s T-shirts are downright mundane to us now, but at that time T-shirts were strictly male underwear and Brando’s brutish, uncouth character was conveyed in part by the absence of a proper button-down shirt over his. He compounds his simmering sexuality by changing shirts in front of the camera, and in the famous “Stella!†scene, his shredded T-shirt actually peels off him lewdly, testament to the fragility of the undergarment:

In Rebel Without a Cause (1955), James Dean and his gang flouted conventions and, like Brando’s character, used dress (or rather, the state of near undress) to signal their outsider, somewhat misfit communal status, with all the sexy implications the forbidden carries.

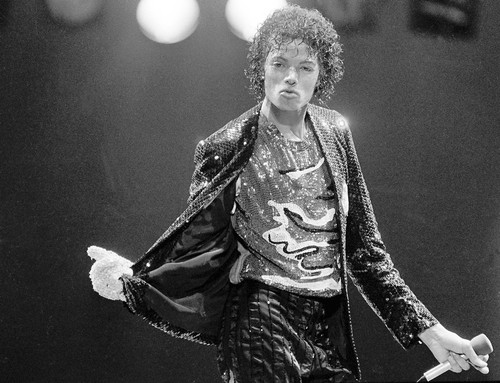

As the posters for Liz Taylor in BUtterfield 8 did, the T-shirt or undershirt is paired with an outdoor coat for heightened impact.

Even in recent years, there is an increasing backlash to men displaying their underwear. This latest effort by some citizens and politicians to enact laws forbidding sagging jeans that expose boxers is tinged with a distinctly racial tone, as it’s primarily young black men who follow this trend (conceived in minority-heavy prisons where inmates may not wear belts) and who are therefore targeted with the desired sartorial censorship.

Obviously the idea of the forbidden, the secret, the hidden, still offends and titillates today, and Galliano’s collection is testament to this enduring tension. With a self-conscious nod to vintage lingerie, the prominently featured seamed stockings are an erotic, romantic reference to outdated style. No longer deemed essential for respectability, girdles, garters, and conical bullet bras are relegated to pure camp and arousal, which some women choose to wear as a provocative statement that we all understand to be vintage. Dior’s collection reclaims the dampened vulgarity by exposing the contraptions that hold stockings up, that support and distort the body for added curious eroticism, and perhaps even a sense of uncomfortable indecency, a feat in this desensitized age of exposed bra straps, halter tops and micro miniskirts. Though there are grumbles relating to the appropriation of underwear worn as outerwear even today, this is not a new phenomenon by any stretch. Attitudes toward the naked body and sexuality, notions of privacy, discretion and sexual identification are constantly changing and fashion changes with them. Return for Part Deux next week for more on underwear as outerwear, this time as a political statement….

FURTHER READING:

- “Are Your Jeans Sagging? Go Directly to Jail.†NY Times, 8/30/07

- 20th century silhouette and support timeline

- Fashion, Desire and Anxiety, by Rebecca Arnold

- 1950s underwear and ads at Fashion-era.com

4 comments

para kazanmanın yolları says:

Aug 7, 2011

“This was such a pleasure to read. I appeciate the contrast and comparisions.”

Jill (Live Webcam Porn) says:

Jan 6, 2010

This was such a pleasure to read. I appeciate the contrast and comparisions.

Tiffbit says:

Dec 30, 2009

In retrospective, the mid-century had objets to control the way women looked to control society. Although today’s runway looks are most of the time described as “unbelievable”, “shocking”, etc, there’s always the underlying aspect of looking “sexy” instead of mid-century “appropriate”. I’ve enjoyed the assessment.

Karina says:

Sep 3, 2009

Nobody is titillated by bodies, anymore — even girls here in God’s Country wear it as though it’s flannel. I suspect that Galliano’s fetish has less to do with the tension between modesty and sexiness and more about the similarities of these sadistic, confining garments in Spandex and their leather counterparts — taking “forbidden” in a whole ‘nuther direction. Which may be your point.