The Politics of Mannequins, Part III – Mannequins in Art

by Tove Hermanson on Mar 2, 2010 • 5:40 pm 2 CommentsUntil the article I recently read, mannequins in their practical form held little interest for me; however mannequins in art have always attracted me, most likely due to my obsession with fashion coupled with my fascination with unsettling representations of people (and who doesn’t love to be unsettled?). Incorporating mannequins — invented to market and sell fashion ideas — into non-consumerist functions is another aspect of mannequin art I find appealing.

Artists James Rosenquist (1933-), Jasper Johns (1930-), Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), and Andy Warhol (1928-1987) were all window display artists in their early careers, in addition to (previously mentioned) author L. Frank Baum (1856-1919), so it should be no surprise that there’s a significant amount of crossover between “high art” works incorporating the lowly, functional mannequin, and “low art” window displays incorporating fine art. Modern art provided inspiration for window designers such as Robert Currie (1948-1993) and Candy Pratts-Price (1950-), who injected surrealist elements of violence, sex, and macabre humor into their 1970s windows. Artists like Salvador Dalà (1904-1989) and Andy Warhol and industrial designers like Donald Deskey (1894-1989) and Henry Dreyfuss (1904-1972) also played major roles in transmitting 20th-century movements such as minimalism and pop art to the audience on the street. Barneys’ famous windows, overseen by eccentric Simon Doonan (1954-), have incorporated works by Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger (1945-) and often reference pop culture, as in this 2009 display with traditional female mannequin bodies topped with (arguably lowbrow) Mad Magazine’s “Spy vs. Spy” characature heads to show off trenchcoats:

The window below attracted much criticism in 2009 for Barneys, though I personally think there’s something amazing about conveying such extreme movement — mimicking gangster movies — in a frozen tableau:

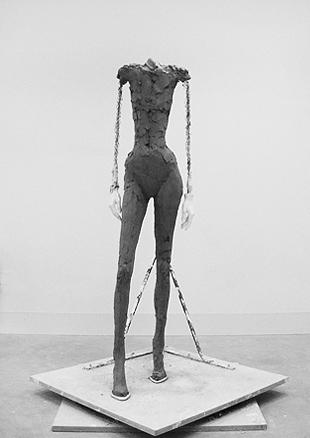

The Pucci Mannequin company (mentioned before) collaborated with many “high art” artists. Ruben Toledo (1960-) collaborated with Pucci on a “Shapes” series of mannequins for the fashion collection of Ruben’s wife, Isabel (1961-):

As you can see, the dimensions of these forms are atypical for mannequins which traditionally mimic the body type idealized at the time of production. By contrast, “Birdie” is curvy, hippy, and even has a little belly. Though she probably resembles the bodies of living, breathing women more accurately than traditional spindly mannequins, she looks startlingly disproportionate because we’re not used to seeing “real woman” proportions glorified in mannequins. (The obvious follow-up question should be: why?) Designed to be functional displays, I think these work as controversial art in their own right. Most artists who use mannequins do not attempt to be realistic, though.

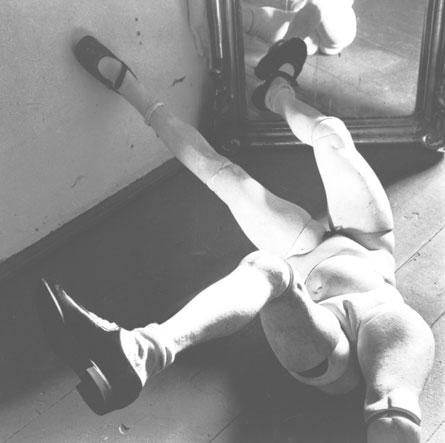

Hans Bellmer (1902 – 1975) anonymously published an amazing “Doll Project” (a.k.a. “die puppe“) book in 1934 consisting of photos of a crippled-looking, armless, peg-legged young female mannequin posed in 10 tableaux. Because of the high contrast shadows and close-cropped frame, my mind wavers between seeing a decrepit doll and believing it’s an unfortunate triple amputee, perhaps in a war-torn country (and in fact the Doll Project was a direct criticism of the growing Nazi oppression and violence Bellmer observed):

Bellmer’s later work became more abstract and involved arranging increasingly mutated human forms in progressively unconventional poses (often focusing on female genitalia, which store mannequins still only attempt in nipple realism — see my earlier segment for more on this). Ultimately forced to flee Nazi Germany, he was welcomed by the Parisian Surrealists who appreciated his odd style (bless them!).

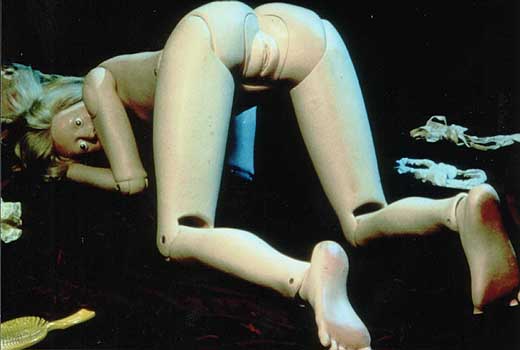

Cindy Sherman (1954-), known for her literally transforming self portraiture, has also experimented wildly with mannequins and dolls in her photographs. Though the joints of her mannequins are pronounced, calling attention to their inanimate-ness, they are often outfitted with exaggerated or hyper-realistic sexual and reproductive organs, wrinkles and body hair, as store mannequins deliberately omit. Sherman calls attention to our simultaneous discomfort and obsession with self-image: the ravages of age, our preoccupation with hair removal, and our uneasiness with blurred gender lines, as in “Untitled #250” (1992):

Store mannequins are created to be sexy — sex sells, after all — but Sherman pushes this concept to depict dolls in explicitly erotic situations that are somehow distinctly un-sexy, also calling to mind a doll’s (unadvertised) function as a child’s tool to explore sexuality. The doll in “Untitled Film Still #255” (1992) has been outfitted with realistic (if hairless) genitalia and is surrounded by ordinary household objects (hairbrush, rope) that, in the context of the doll’s doggy-style position, become S&M objects of torture and pleasure:

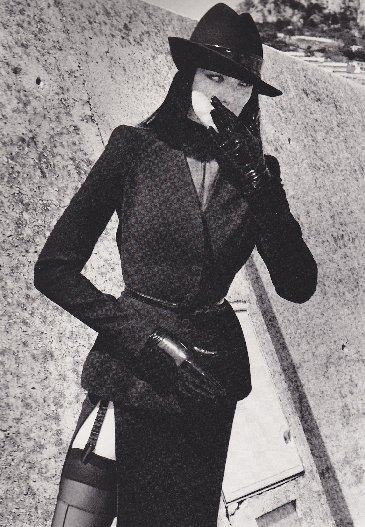

Helmut Newton has collaborated with mannequin manufacturers since the 1960s to create “twins” for live models, used with or instead of live models. Interestingly, he features many women with visible imperfections like scars which humanize them, while gashes at joints betray mannequins. He draws your attention to the falseness of the fashion industry, the ridiculous standards of beauty, but he revels in it too.

Violetta (below) confronts her doppelgänger, even while she mimics the imposter’s oddly positioned arm. Who (or what) is more useful in the fashion industry, flesh or fiberglass?

Newton experimented with the roles of mannequins and flesh-and-blood models, often pairing realistic dummies and women together (as above) or posing mannequins in public spaces and models in interior settings to create subtle disorientation. He frequently places human models in stiff, awkward positions as though their bodies had limited range of motion like mannequins (or more morbidly, like cadavers):

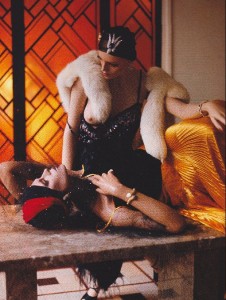

In “Store Dummies I” (French Vogue, 1976), two incredibly realistic dress forms are posed in a Sapphic moment of seduction, one on a marble slab (morgue reference?) and the other in a state of frozen dishabille:

I love how Newton pokes fun at the fashion industry, places lifeless forms in vulgar poses to sell clothes, drawing an uncomfortable parallel between glamor mannequins, vapid models, and outright sex dolls. And speaking of sex dolls….

I must mention sculptor Allen Jones (1937-), whom I discovered while browsing in an amazing art-and-literature bookstore in Montmartre several years ago. Jones is infamous for his pieces depicting forniphilia — where sexual (S&M) objectification is manifested in a submissive partner acting as a piece of furniture. Jones substitutes human submissives acting as inanimate objects with inanimate mannequins depicting human submissives acting as inanimate objects (got that?). These women (more voluptuous than standard mannequins, closer to blow up doll proportions) are sex objects and domestic objects at once, two roles (three if we’re including being an “object”) women have struggled to define themselves outside of:

I must also point out the rug, indicative of the era and also deliciously vulgar in its associations with bear skin glamor shots and art historical connotations of pubic hair.

Predictably Jones’ creations have been deemed misogynistic by many. He has humorously responded, “I was reflecting on and commenting on exactly the same situation that was the source of the feminist movement. It was unfortunate for me that I produced the perfect image for them to show how women were being objectified.” Gotta love the self-aware man!

If Jones’ pieces look vaguely familiar, it’s probably because Stanley Kubric attempted to mimic them in the infamous Korova Milk Bar for his distopian A Clockwork Orange (1971), after Jones refused to work for free. Kubric’s versions are stripped of their fetish gear and props (cushions and glass tabletop) and are monochromatic white, establishing a visual relationship with the white-clad gang of the film and with classical marble sculpture:

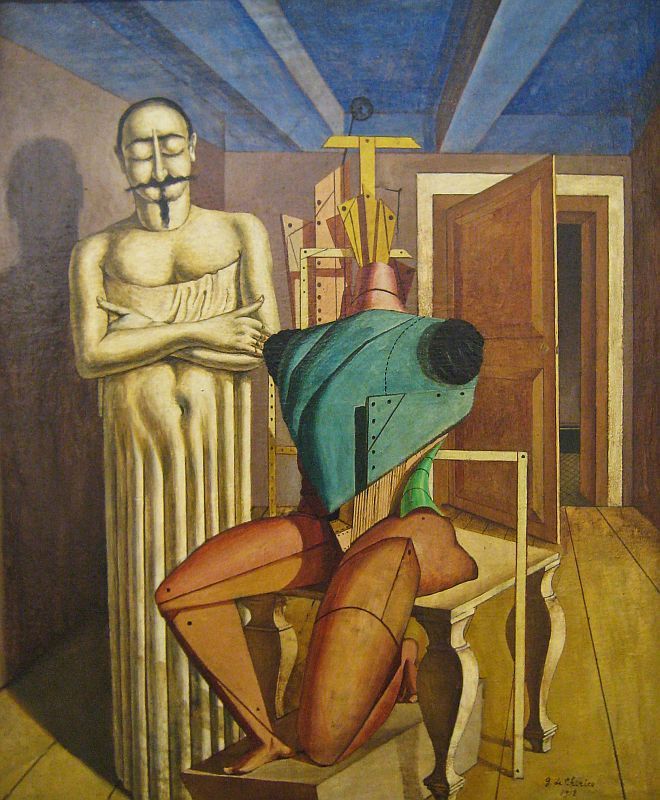

Early Surrealist painter Giorgio De Chirico (1888 – 1978) made a similar comparison many decades earlier, between stone busts and more animate (if more abstract), jointed, mannequin-like figures. “Il Ritornante” (1918) depicts a drowsy marble bust with realistic facial hair and a dummy composed of mismatched scrap materials. It’s unclear if one of the figures is actually animated and has created the other, but regardless, a strong connection is made between the structure of the room itself and the bodies: one is a caryatid-like supportive column and the other appears to be made of ribbed sheet metal, wooden blocks, and T-square rulers. The flattened perspective makes it even more difficult to distinguish the human forms in the foreground from the cluttered tower of planks and door in the background, visually uniting the human-ish forms with the room’s architecture:

In “The Disquieting Muses” from the same year, De Chirico turned the column fluting into drapes of himation robes, topped with dress form knobs that resemble disproportionate heads. Again, there are buildings in the background and a more fully realized Grecian-like statue that has a similarly blank, oval head, blurring lines between the structures of buildings, statues, mannequins and humans:

Fellow Surrealist and Dadaist Man Ray (1890-1976) experimented with mannequins in photography around the same time. His father had fittingly worked in the New York garment industry and as a tailor, his mother was a seamstress. Times critic Sarah Rosenberg recently wrote, “Dada artists used mannequin parts… as a reflection of consumer culture and war trauma.” The mannequin below appears to be ensconced in a tangled wire bubble reminiscent of barbed wire, with a ridiculous fake mustache (disguise?) and a protective metal corset. It’s not hard to draw comparisons to Man Ray’s persecuted Russian Jewish immigrant history, which he went to great lengths to conceal even after achieving success.

“Mannequin with a bird cage over her head” (1938-66) is a similarly posed naked mannequin that has been gagged, her entire head and shoulders caged, some tiny arm-like appendages reaching out of one side. Places where “private” hair grows — armpits, crotch — have been decorated with whimsical flowers and feathers. It’s sinister and silly at once:

As mannequins have been anatomically perfected and increasingly incorporated into the public sphere via window displays, they have also been utilized by artists other than designers and window dressers. Humans are obsessed with self-representation: in 2-dimensional portraiture, 3-dimensional dummies, and even moving mechanical droids. Even while we understand they’re inanimate objects, when mutated, manipulated, or uncannily accurate, they have tremendous power to attract and repel (I’ll wager some readers were disturbed by at least one image I included). Like few other functional objects, they have the inherent ability to act as commentary on beauty standards, surgical manipulation, sexual taboos, persecution, and the very relationship of reality to its distorted image. Some day I’ll have my own mannequin collection, to dangle from my ceilings and to dress up and undress and to play with, but in the meantime, I’ll content myself with powerful images like these.

Additional resources:

- “Mannequins: Fantasy Figures of High Fashion” by Emily and Per Ola d ‘Aulaire, Smithsonian Magazine , April 1991

- Fashion Windows “Historical Overview of Mannequins“

- The Show Window periodical magazine, edited by L. Frank Baum

2 comments

garconniere says:

Jan 15, 2013

phenomenal series, phenomenal insights.

Ms. T says:

Mar 14, 2010

I like to think of mannequins as part of the garments themselves. They resemble who’s wearing them. It’s also a slightly twisted non-verbal conversation between the designers vision and the consumer. For instance, when a consumer sees a jacket, they often picture themselves in it first.

-T