Just saw the Susan Meiselas exhibit at the International Center of Photography. Though none of her carnie stripper photos were there, her pictures of the popular insurrection Nicaragua (1978-79) and Kurdistan were stunning, with an eerie unprofessional air about many of them.

From the Nicaragua series there was one photo of a young woman in a red dress pushing a tarped body strapped to a rickety cart as she looked over her shoulder backwards. A video taken years later captured the story of the woman who revealed the body was her husband who’d been shot, she was desperate to bury him with as much dignity as possible. She begged neighbors for a box in which to bury him, but the best she could get was a plank, onto which she strapped him, wrapped in a cloth or sheet. The picture was taken as she was rolling him alone to his resting place, and she recounted how she was shot at by low flying helicopters while making the journey. She pointed out that she was especially visible because of her bright red dress, which had struck me in the photo as being particularly vivid and pretty in an otherwise desolate landscape of muted tones of rubble and dust, but her story added that additional layer of urgency: that her bright dress (perhaps her Sunday best for the private funeral, though she didn’t specify) actually became a liability to her own life as she was forced to dive under the corpse of her murdered husband’s (less conspicuous) body for cover.

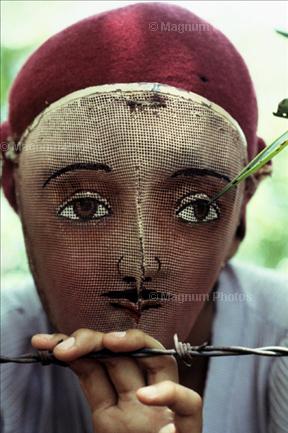

Though many of the rebels covered their faces with handkerchiefs and rags– which is very menacing in and of itself– a traditional Indian dance mask was adopted by the Sandinistas in Monimbo, Nicaragua. These masks were egg-shaped and made of mesh painted with a rather blank, sexless, wide-eyed doll-like expression that completely obscured the wearer’s true features and facial shape while allowing them visibility. This served the dual purpose of concealing rebels’ identities while simultaneously advertising their allegiance with their political movement as a more traditional army would with a more complete uniform. The mask also struck me as being extremely similar to a fencing mask I’d seen in one of my favorite East Village shops Obscura just yesterday.

In Kurdistan, Northern Iraq Meiselas took a photo of an uncovered mass grave and a woman looking pitifully down at it. Horror of the subject matter aside, I was puzzled by the discrepancy between the decomposition of the bodies– which had been reduced to mere skeletons– and their clothes, which seemed to be mostly in tact. Textiles are notoriously fragile– how did they remain unscathed?

My final thought was on a photo of another grave site, where the clothes of the deceased had been carefully laid out as makeshift grave markers (photo here not the actual one I saw, but same gist). Without reading the caption, it just looked like a bunch of dirty clothes strewn on the ground. Though the items had been used as a shabby substitution for more permanent gravestones, the shirts and pants laid out like a mother might lay an outfit on her child’s bed was inventive, effective, and beautifully touching.

Is anyone else aware of situations where clothes were used for grave markers?