Due to a coveted invitation to my friend’s tea party this weekend, I have that genteel social event on my mind. And since I always have costume on my mind as well, it’s only natural that I should want to dissect a portrait of a young woman enjoying the same activity that I shortly will.

Mary Cassatt’s “The Cup of Tea” is a portrait of Cassatt’s sister, Lydia Simpson, wearing a pink gown, circa 1879 (among other date indicators, Lydia’s flat-lying skirt suggests horsehair crinolines underneath, which made a brief return to fashion between 1876 and 1882 before being replaced by the bulkier bustle). “Tea gowns,†essential garments of the late 19th and early 20th century wardrobes and invented by the tea obsessed English, are frilly, decorative, and also comfortable, often achieved by a looser fit uncommon in other dresses of the 19th century. Though Lydia’s dress appears rather fitted — you can clearly see the outline of her corset at her tiny waist and gently bulging belly — it’s possible that her arm is blocking our view of a looser fitting back, allowing her to recline more comfortably. The profile of a stiffer seated subject was famously used to portray an older, darker, more somber portrait: that of “Whistler’s Mother,†officially entitled the more clinical “Arrangement in Grey and Black: The Artist’s Mother†(1871), and I doubt it’s a coincidence that Whistler’s mum was painted just a few years earlier than Cassatt’s sis.

A small enough amount of lace is present in the Lydia’s cuffs so that it’s conceivable that handmade lace — a precious luxury item — was used. However, the appearance of a Great Exhibition in Paris just a year before this portrait helped popularized machine-made lace, making it more accessible and far more affordable, so it is reasonable to think that Lydia wears some. The rich silk-satin fabric advertises Lydia’s wealth, and though it is possible that Lydia’s dress was sewn with the help of the sewing machine (a major asset to the fashion industry since the 1840s), the upper class still preferred the personally designed, tailored and unique looks generated by the haute couture industry.

Charles Frederick Worth (1827-1893) was an Englishman who pioneered the haute couture experience with his House of Worth located in Paris. Founded 1858, his success corresponded with France’s Second Empire which devoted considerable energy to rebuilding the luxury textile / fashion trades Paris had been known for before the French Revolution (1789 – 99), during which all things seen as bourgeois were attacked, very much including high fashion. Worth not only capitalized upon the climbing demand for sumptuous clothes, he absolutely revolutionized the dress purchasing experience, turning it into a social event for the privileged. Instead of being visited by a doting tailor, as in the past, a 19th century woman in need of a new dress would go to her fashion house (others opened after Worth’s, though his remains the most acclaimed to this day). There she would be received in a decadent parlor filled with other wealthy society ladies, and a fashion show would parade before them, to select the styles they desired. Consultations on fabrics and trimmings would follow (these finishing touches would distinguish the same dress style purchased by different women), measurements taken, the final product being a unique work of wearable art. The elegant simplicity of Lydia’s gown makes it a possible product of the House of Worth itself.

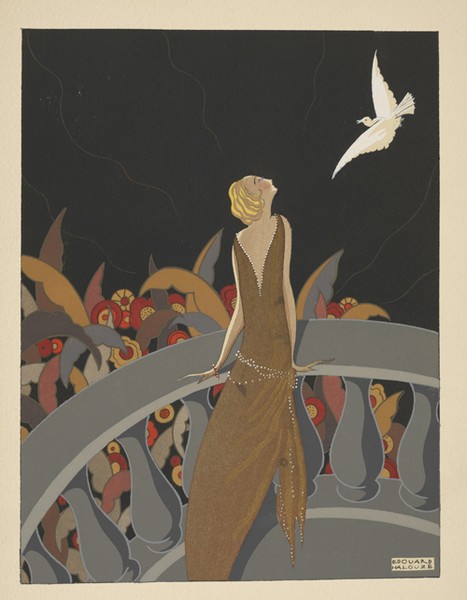

Here is a gown from the House of Worth just a few years after Cassatt’s painting. From the Met’s caption: “Lavish textiles were not only used for evening wear in Worth’s designs, as this day dress of cut and uncut voided velvet attests. The ensemble also provides an example of Worth’s practice of incorporating elements of historic dress in his designs. The large scale of the pomegranate and floral motif follow the style of Louis XIV textile patterns.”

During the High Victorian Period (1850-1885), a strict regulation of clothes was maintained. According to these laws of dress, Lydia’s high neckline, three-quarter length sleeves and sumptuous fabric show that the portrait captured a moment of the afternoon (as opposed to plunging décolleté with short sleeves which were for fancier evening activities, or if the same dress were made with less refined material like cotton, it would have indicated casual dress for mornings). As the title suggests, the primary purpose of this painting was not portraiture, but the depiction of a popular social ritual. And though Cassatt was American, she frequently depicted bourgeois Parisian society, which, “between 1870 and 1914 was thrown back on its own devices to satisfy its taste for elegance. The Ancien Regime and the Imperial aristocracy, the bourgeoisie enriched by the economic revival, and the spendthrifts, frivolous demi-monde that succeeded to the follies of the Second Empire, all provided an easy prey for the new lords of elegance, the masters of Couture and Fashion,†as Francois Boucher noted.

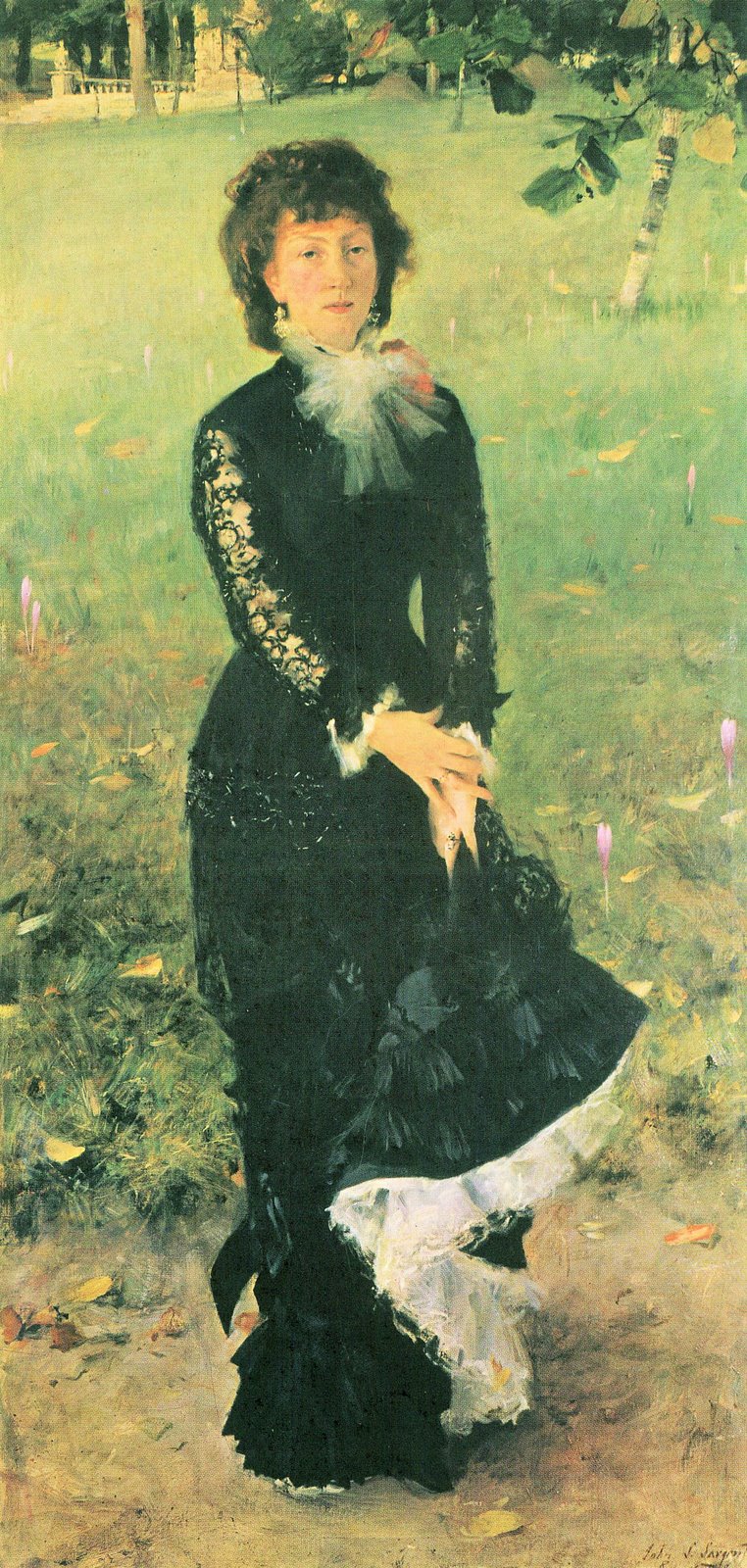

In John Singer Sargent’s “Madame Edouard Pailleron,†also painted in 1879, a similar look is achieved. A small departure is that Lydia wears a tea gown while Mme Pailleron wears a fashionable dress suitable for outdoor activity, and this is confirmed by her grassy surroundings. The same idealized long-waisted hourglass figure is achieved with the same long corset. She lifts her skirts enough to reveal the crinolines we assumed Lydia wore. Where Lydia’s tea gown of soft silk satin was conducive for casual indoor comfort, Mme Pailleron’s stiff dress is probably silk taffeta and more appropriate for formal public appearances. In contrast to Lydia’s ultra-feminine and youthful pink, Mme Pailleron wears somber black, obviously a fashion choice and not imposed on her by rules of mourning (see my earlier post), as she also has a large white tulle bow around her neck and flamboyant red flowers on her shoulder — unacceptable for mourning. In spite of its conservative color, Mme Pailleron’s dress is highly decorated with short, layered ruffles along the hemline (it must’ve sounded divine, rustling with her movements!), a band of beadwork around the hips and neckline, lace sleeves and lace strips draped around the skirt (machine-made, judging from the length and quantity), and taffeta bows on the cuffs and skirt. Though both women have white tulle around their necks and cuffs, that tulle is Lydia’s only dress ornamentation. As expected, the two women seem to be following the same fashion trends, the major differences only being those that can be attributed to different activities.

Lydia’s light but voluminous collar is similar to Mme Pailleron’s of the same year, and Lydia has taken it to an extreme so that it becomes reminiscent of the standing ruffs of the 16th century, which was a major social status symbol, made of that precious lace, laboriously starched, and difficult to keep clean in its proximity to the face:

Revival styles (or “flashback fashion” as I like to call them) was extremely popular in the 1870s, and Lydia seemed to embrace this fascination with the past. Her costume suggests an affinity for Neo-Rococo taste: the soft, curvy lines exaggerated by the hourglass corset, the fitted, three-quarter length sleeves ending in a flurry of bell-shaped white lace, not to mention the vaginal billowing pink silk, are all reminiscent of Fragonard’s Rococo painting “The Swing” (1766). This painting, along with the original Rococo movement a century earlier, was obsessed with the idea of femininity and sexuality in the eyes of the voyeur:

Lydia’s style would have been well noted, as she lived a life where to be a successful society woman, one had to keep up appearances. With the completion of Garnier’s Parisian Opera in 1874, the opera became an important place to see and be seen. Opera glasses were just as often used to observe audience members as they were to watch performers on stage, and usually by the traditional voyeurs: men. Not limited to sexual voyeurism, a man would survey his business competitor’s wife to see how well she was dressed, her appearance a direct reflection of how successful her husband was. Baudelaire wrote that woman was “the object of keenest admiration and curiosity that the picture of life can offer to its contemplator.†Mary Cassatt and the Impressionist art movement was fascinated with this phenomenon, often painting these privileged voyeurs at the Opera. Cassatt continues this theme in “The Cup of Tea,†eliminating her sister’s companion from the composition and making the viewer of the painting Lydia’s voyeur — all the more titillating, perhaps, as tea time was a female ritual that men would not see at all — except in paintings.

The floral theme in “The Cup of Tea†warrants examination as well. Throughout art history, flowers have acted as a visual metaphor for a woman’s sex, and the concept of the femme fleur was especially popular in Victorian times. The melding of the flower in Lydia’s hat with the flowers in the flowerbox behind her is echoed by her bell-shaped cuffs and the rosettes making up her collar, which gives a floral illusion when viewed en masse. Furthermore, the blurred lines between hat flower and flowerbox flower create a physical unity with the house, thus suggesting a traditional psychological unity of woman with the home. Though feminist movements had manifested themselves in both fashion (with the invention of the Bloomer costume in 1849) and politics (with the women’s suffrage movement), it is clear that neither Mary nor Lydia Cassatt subscribed to these radical ideas, instead perpetuating traditional stereotypes of feminine roles in painting and costume.

But enough of Lydia, and on to more important, current issues: what will I wear to my own tea party?

Further Reading:

- “The Cult of the Tea Gownâ€

- “Tea Trot” photo montage, NY Times

- “How Tea-Mania Flooded Britain,” Telegraph.co.uk

2 comments

Cathy Anderson says:

Jan 11, 2010

Hwuah! I never knew those one. Thanks for sharing information on tea dresses? Is that the term for there?

By the way, I love the gown from the House of Worth. I super super like it! Ancient look with a touch of elegance. Excellent! Just wondering how uneasy to dress like those. I bet they are so heavy based on the cloth material. Just glad I’m not born on those days.lol. Though I’m not against or any of it ‘coz it stil looks good, just that, I don’t think I can handle long on those kind of dresses.

gillian says:

Jul 24, 2009

Don’t forget tea dances, which started out in the bourgeois millieu you describe, but became significant rallying points for the queer community in the post-Stonewall era. Although the “T-Dances” in Provincetown and San Fran today don’t include quite as many ruffles, the idea is still to reterritorialize the gentility you’re talking about here!