Subversion in Trompe L’oeil, Graffiti, and Fashion

by Tove Hermanson on Feb 1, 2011 • 1:18 pm 1 CommentComing from an Art History background with all its unfortunate snooty and consumerist associations (fashion shares these themes, I’m afraid), I’ve recently become obsessed with its subculture offshoot, the publicly accessible graffiti (or “street art”) movement. Long fascinated by graffiti, I’ve recently gone on a binge, going out of my way to walk around Pilsen while visiting my friend in Chicago (it’s known for its street art; you can see my photos here), thumbing through my Banksy book, and watching documentaries like Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010) and Beautiful Losers (2008). I was especially captivated by the “Underbelly Project,” a unidentified underground “gallery” created in an abandoned New York subway station whose “curators” asked dozens of guest graffiti artists to creatively deface walls. You’ll thank me for recommending the slideshow of this installation-specific “exhibit.”

Most graffiti is site-specific, incorporating unique aspects of a location right into the art; this lends it to the use of trompe l’oeil, blurring the lines of the environment and the art (Marcel Duchamp, of course, pioneered this technique in the early 20th century). Graffiti artist Banksy in particular employs trompe l’oeil in many of his works. For example, the maid below is “sweeping” on a chalky wall in Chalk Farm (a London neighborhood, not an actual chalk farm), riffing on the location in multiple ways:

And the following, more bitterly ironic example, painted directly onto the wall built by Israel which separates the occupied Palestine territories from Israel (see more of Banksy’s Palestine wall murals here), drawing attention to the oppressive concrete barrier but also hinting at the potential for its destruction:

The Ancient Greeks, and painters in the Baroque and Renaissance periods also loved to trick viewers, and they often incorporated “fabric” into part of the illusion:

Elsa Schiaparelli famously adopted the trompe l’oeil technique and created optical illusions of fashion embellishments, without actually attaching embellishments, as in this knit sweater with “bow” and “cuffs”:

This is comically jarring — we often take our expectations for granted (in this case, we expect multiple layers of different materials) — and we only realize we had assumptions when they prove to be inaccurate. In most cases of trompe l’oeil this is meant to be an amusing realization, but much graffiti art is designed to be more confrontational. As the antithesis of “high art” — produced for wealthy private and corporate patrons — graffiti bears distinctly seedier, subversive connotations. It’s frequently associated with (and often indistinguishable from) out-and-out vandalism, gang tags, and is often linked in people’s minds to the perpetuation of a cycle of low-income and high-crime neighborhoods.

These sinister connotations are conveyed in Alexander McQueen‘s Spring/Summer 1999 fashion show, in which a windswept and vulnerable Shalom Harlow is seemingly attacked by mechanical spraypaint robots. Oh yeah.

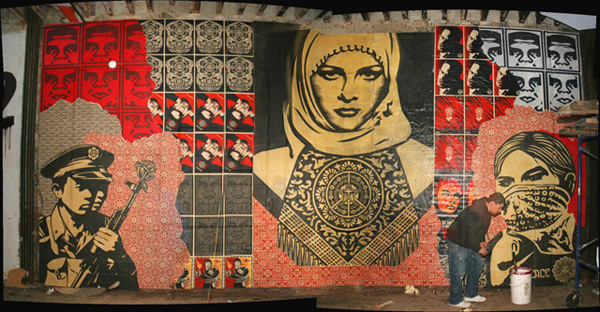

Like trompe l’oeil that brings to light one’s own unconscious expectations, the negative and violent connotations of graffiti are exposed when you simply modify the vocabulary: call a graffitied wall a “mural,” and the sinister overtones are eradicated, but why? Because murals are legal? What, besides red tape, is the difference between graffiti and murals? Perhaps to combat the negative stereotypes (perhaps not), “graffiti” is increasingly dubbed “street art” which not only makes it more palatable for general consumption (“street art” is actually appearing in some galleries now), but it more easily encompasses spray painting and wall collage, such as Shepard Fairey creates. Fairey has had a significant hand in “legitimizing” graffiti as he mimics political propaganda posters in a Dada-esque manner, with trompe l’oeil layers of “torn” “posters,” some of which are modeled on actual posters he has already created as solo pieces. Indeed, most of his graffiti is overtly political (as is Banksy’s), urging citizen activism, and inherent in his chosen medium, civil disobedience. (He is perhaps best known these days for his iconic “Hope” Obama posters; but this has not shielded him from vandalism convictions.) In the snapshot below, Fairey’s familiar Andre the Giant “Obey” posters appear to be under / over other crumbling posters and wallpaper / textile illusions, the “layers” drawing attention to the mutable impermanence of his own art (and by extension, political regimes):

Part of what many graffiti artists are commenting on with their acts of guerrilla public art is the lack of choice the population has in ingesting the images that bombard our senses. Billboards on the roads, commercials in elevators, propaganda posters along sidewalks, these all assault us in public places legally, though their purpose is not the egalitarian sharing of public art so much as it is to compel us to consume products for someone else’s personal/ corporate profit. Many graffiti artists question authority at large, and the commercial art scene. Transgressive in its subversive messages and technical vandalism, most graffiti artists produce works of art at their own expense for free public enjoyment, or perhaps public awareness of social issues. The NYTimes article on the Underbelly Project points out that if the artists had been caught, they could’ve be charged with trespassing and possibly terrorism. Workhorse, one of the project organizers said, “There is a certain type of person that the urban art movement has bred that enjoys the adventure as much as the art. Where else do you see a creative person risking themselves legally, financially, physically and creatively?†And often knowing the fruits of their risky labor will be removed / painted over! You gotta respect the commitment.

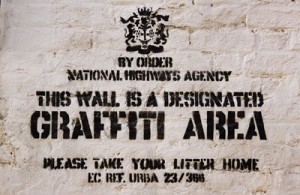

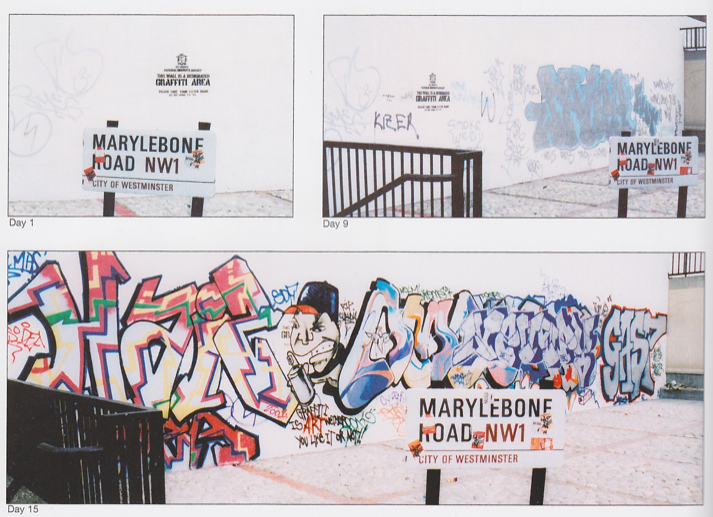

I thoroughly enjoy the temporary nature of graffiti. Anything that can be painted can be painted over — and if its message is provocative and in an especially visible locale, it’s especially likely to be speedily removed. Something that’s fun about Banksy’s book Wall and Piece is that there are multiple photos of the same wall with timestamps. Bansky favors this approach with projects in which his graffiti invites more graffiti, as with this faux-official stamp that subverts the very concept that graffiti is illegal by making it appear legally sanctioned:

Here is one of the walls with this stencil, on Day 1, Day 9, and Day 15:

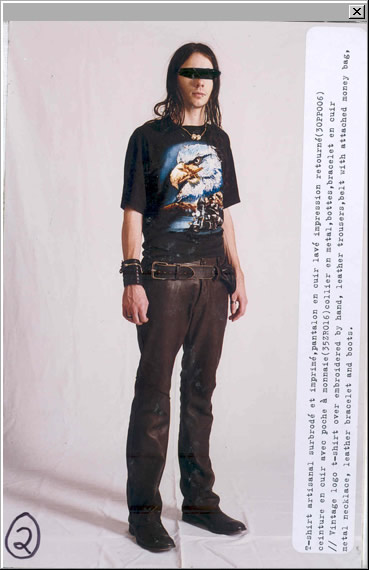

Graffiti walls have limited shelf lives, being exposed to the harsh natural elements and graffiti-removal campaigns. This mimics the impermanent nature of fabric which, textile conservators will tell you, is startlingly fragile. The conceptual fashion house Maison Martin Margiela is known for embracing fabric decay, exaggerating the telltale signs of the passage of time rather than suppressing them. Many of their pieces are painted white: this isn’t traditional “whitewashing” to cover up imperfections, but rather to emphasize the wrinkle fault lines and chips of exposed contrasting color underneath, as the items are broken in. The example below is painted dark, but achieves the same aging effect:

Here’s a closeup of the pants where the belt and knees have already worn away some of the dark paint:

There has been increasing cross-over between fashion and graffiti in the last couple of decades. New York graffiti artist Erni Vales collaborated on the design of limited-edition handbags for Aleya NY. And Apparel Search noted “…[Marc] Ecko won a court battle with New York City when he set out to launch a graffiti fest in New York City several years ago. Ecko, who built a successful apparel company that was founded in 1993, began with just six t-shirts and a can of spray paint. His empire now has approximately six brands under its fashion umbrella, and includes a range of fashions from contemporary styles to t-shirts, denim, fleece, and beyond.”

And I recently stumbled upon this Protacico bespoke hand painted graffiti suit that I rather fancy:

It reminds me just a little of that admittedly terrible Mentos commercial from the ’90s… (you know you want to watch it again):

The haphazard, distinctly urban effect of the neon graffiti print belies the demure cut of this Moschino summer dress in an interesting contradiction:

Jay-Z was recently on The Daily Show wearing a more restrained Marc Jacobs‘ painted mohair sweater:

I love the single stripe that wraps around the back, as though it were a drive-by person-painting:

And speaking of person-painting, take a gander at the Louis Vuitton ad from a couple years ago….

If you look at the bag itself (ignore the smiling naked man for a sec), it’s more in the style of graffiti tagging, where the artist writes his name (in this case, Stephen Sprouse‘s sponsoring company’s name) over and over. While I myself don’t care for this product, I appreciate the translation of a sprayed tag indicating turf property, and painted (albeit designer) moniker indicating product design property:

As graffiti is adopted by the commercial world, it is slowly gaining (corporate) credibility, which has pros and cons for a subversive movement. Distinctly mainstream Women’s Wear Daily informed me that Dude’s Factory in Berlin “asks a different artist or artistic team to redesign the streetwear brands’ entire visuals for its collection of T-shirts, sweaters and hoodies” each month, incorporating site-specific graffiti art to create a backdrop for items for sale.

If you can’t tell, I have mixed feelings about the appropriation of graffiti by corporate ventures: on one hand, I genuinely like the graphic style of street art, so products incorporating it appeal to me; on the other hand, it seems antithetical to the free, urban art movement to participate in collaborations with high end designers and boutiques. But an inherent trait of graffiti that I think will preserve its subversive, edgy, anti-consumerist roots is that it will remain a DIY art that anyone with a sharpie / paint can / printer / glue could imitate. I just might paint my own damn clothes Mr. Jacobs, thank you very much!

For excellent DIY fashion blogs, check these out (and share, if you know some more!):

1 comment

Eli says:

Mar 2, 2011

Graffiti is legit, I love that art style.